The Truth About the IT Job Market—Are Software Jobs Really Disappearing?

Indeed’s job index paints a grim picture, but long-term data tells a different story. Here’s what’s really happening.

Today’s article takes 14 minutes to read.

Key Takeaways

In the news: Housing Market Faces Uncertainty – Home sales hit a 30-year low in 2024, with 73,000 homes pulled off the market in December alone. Sellers are holding out for better conditions, while buyers wait for prices to drop.

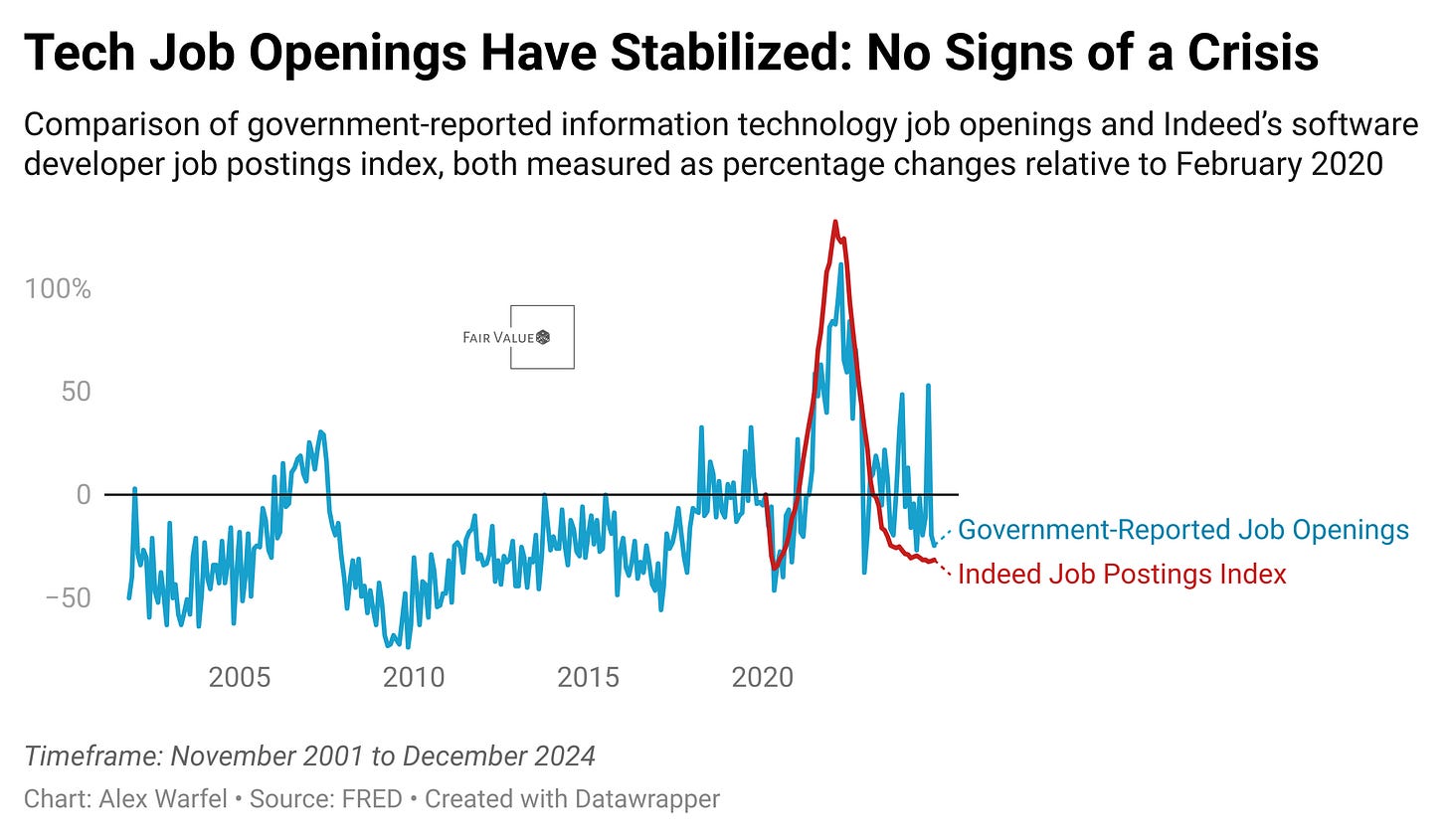

Chart of the week: IT Job Openings Are Normalizing, Not Collapsing – Despite fears that AI is eliminating software jobs, BLS data shows IT job openings are within historical norms. Unlike Indeed’s index, which only tracks changes since 2020, the government’s dataset provides over two decades of context.

Beyond bias: Survivorship Bias in Investing and Housing – We hear about startup success stories and skyrocketing home values but ignore the failures. Research shows that 90% of startups fail, and housing markets can stagnate for years. Recognizing this bias helps in making smarter financial decisions.

Building wealth: The Power of an ‘Opportunity Fund’ – Instead of saving for an “emergency fund,” reframe it as an “opportunity fund.” This mindset shift makes saving feel like a step toward freedom, not just a safety net. Behavioral research shows framing affects motivation.

Historical perspective: The Economics of Piracy in Colonial America – Before the U.S. was founded, piracy thrived along the East Coast, disrupting trade and fueling underground economies. Blackbeard’s blockade of Charleston and the Pirate Republic of Nassau were economic forces in their own right.

Literature review: AI Forecasts Face Investor Skepticism – AI-driven stock predictions reduce perceived credibility (-0.257, p = 0.001), especially among financially literate investors. Hybrid AI-human forecasts perform slightly better but still lag traditional analysts in trust.

In the news

More Homes Are Being Pulled Off the Market

73,000 homes were delisted in December 2024, a 64% increase from the year before.

Homeowners aren’t ready to drop prices and are waiting for better conditions in the spring.

Home sales hit a 30-year low in 2024, even as inventory rose 16% year-over-year.

If you’re buying, more homes may hit the market in the coming months, potentially leading to price cuts. But sellers might hold firm for now.

Home Prices Haven’t Fallen Much—Yet

Despite weak demand, home prices haven’t dropped significantly because sellers are reluctant to accept lower offers.

Many homeowners are locked into ultra-low mortgage rates and don’t want to sell unless absolutely necessary.

Builders are struggling to sell new homes even after making them smaller and offering mortgage rate buy-downs.

If you’re waiting for a big price drop, you might have to be patient. If sellers start cutting prices, it will likely happen later in 2025.

Rent Prices Are Set to Rise

A flood of new apartments in 2023-2024 briefly lowered rents, but that supply is drying up.

More people are renting longer due to high mortgage rates, increasing demand.

Every major metro area is expected to see rent increases by the end of 2025.

If you’re renting, expect prices to go up, especially in cities where construction is slowing. Lock in your lease soon, before rates climb.

Zoning and Regulations Are Making Housing More Expensive

Strict zoning laws in high-demand areas have restricted new housing development, driving up costs.

Historically, these laws were designed to keep certain groups out of wealthier areas.

Even progressive states like California are temporarily suspending regulations to speed up homebuilding.

The government is finally paying attention to the problem, but changes won’t happen overnight. Supply constraints will likely keep prices high in many cities.

Interest Rates and Government Policies Will Shape the Market

Mortgage rates hit 7% again in late 2024, keeping many buyers on the sidelines.

President Trump’s tariff policies could increase the cost of building materials and slow new construction.

His immigration policies could limit the labor force, making homebuilding even slower and more expensive.

If rates drop later in 2025, home buying may become more attractive. But if government policies make building more expensive, both home prices and rent could stay high.

Chart of the week

There’s been a lot of panic about the decline in Indeed’s software development job postings index, with some claiming it signals that AI is eliminating software engineering jobs. However, this argument is based on a dataset with a limited history. Indeed’s job postings index only measures changes relative to February 2020, meaning it lacks long-term historical context. To get a broader picture, I compared this index to government-reported job openings data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), which has been collected since 2001 through the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS). The BLS survey gathers data from roughly 21,000 businesses across various industries, making it a more reliable source for understanding long-term employment trends. When we look at this broader dataset, it’s clear that hiring in the information technology sector has stabilized at historically normal levels—not collapsed.

The notion that computer science is no longer a viable career path because of AI is not supported by the data. While job postings have declined from their pandemic-era highs, they remain within the range of normal market fluctuations. In fact, historical data shows that IT hiring has been through much worse downturns before. Following the 2008 financial crisis, job openings in the sector were down 70% compared to February 2020 levels—far more severe than the current 25% or so decline reported by Indeed. Software development jobs could be less prevalent due to automation and shifting job responsibilities, but the overall number of IT job openings remains steady. Instead of signaling the death of software development as a profession, these trends suggest that the industry is undergoing a natural transformation, just as it has through previous technological shifts.

Beyond bias

Survivorship bias is a cognitive distortion that occurs when we focus on the successes that remain visible while ignoring the many failures that have disappeared from view. This bias skews our understanding of risk and opportunity, particularly in investing, entrepreneurship, and real estate. In the startup world, for example, we frequently hear about companies like Apple and Amazon that began in garages and became industry giants, but we rarely see the thousands of startups that fail each year due to market forces, poor management, or lack of funding (Moskowitz & Vissing-Jorgensen, 2002). Similarly, in the housing market, people tend to recall stories of properties appreciating dramatically, while overlooking the many cases where home values stagnated, declined, or became financial burdens due to high maintenance costs and property taxes (Case & Shiller, 2003). The same phenomenon occurs with small businesses—aspiring entrepreneurs hear about the local café that became a neighborhood staple but rarely consider the vast number of restaurants that quietly shut down within their first five years (SBA, 2023). This incomplete picture leads to overconfidence, as investors and entrepreneurs assume that success is more common than it actually is.

To counter survivorship bias, investors and decision-makers must actively seek out and analyze failure data rather than just success stories. One way to do this is by researching historical failure rates within industries before making financial commitments. For instance, those considering investing in startups should study venture capital statistics, which reveal that approximately 90% of startups fail, with only a handful generating significant returns (Startup Genome, 2022). Similarly, prospective homebuyers should look beyond rising home prices and consider factors like past housing market crashes, potential long-term costs, and liquidity risks associated with real estate (Shiller, 2015). Entrepreneurs launching small businesses can reduce risk by studying why similar ventures have failed, adjusting their strategies to account for market shifts, competition, and operational challenges.

Building wealth

Most people are told to build up an emergency fund, but the term itself can feel discouraging—who wants to set aside money just to prepare for something bad? A simple psychological shift can make saving more appealing: instead of an emergency fund, think of it as an opportunity fund. This money still acts as a financial cushion, but it’s framed as a tool for growth, freedom, and optionality rather than just avoiding disaster. With an opportunity fund, you’re not just bracing for car repairs or medical bills—you’re also preparing for unexpected chances, like investing in a promising business, seizing a great travel deal, or taking a career risk. This subtle change in mindset makes saving feel empowering rather than restrictive.

To implement this, set up a separate high-yield savings account and name it something aspirational, like “Freedom Fund” or “Next Big Move.” Automate regular contributions, just as you would with an emergency fund, but mentally associate the money with potential rather than crisis. If a genuine emergency arises, the money is still available—but you’ll also start viewing your savings as fuel for opportunity rather than just a safety net. Over time, this small mindset shift can increase motivation to save, reduce financial anxiety, and create a proactive relationship with money—helping you build wealth while staying prepared for life’s surprises. Make sure you don’t spend too much of this fund so you are still prepared for emergencies, or perhaps set aside separate “true emergency” funds, but overall this strategy can help reframe the unpleasant task of saving.

Product focus

Take control of your financial future with Rainier FM—your AI-powered financial planning companion. FM stands for Financial Model, and that’s exactly what this app delivers: optimized, data-driven financial plans tailored to your goals. Using advanced optimization techniques and AI-driven insights, Rainier FM helps users navigate everything from retirement planning to wealth building with confidence. Pricing reflects the cost of running the service, but I’m actively gathering feedback to refine and improve it. If this sounds like something you’d find valuable, feel free to reach out or sign up—I’d love to hear what you think as I continue developing the platform!

Historical perspective: The Economics of Piracy on the East Coast Before America Was Founded

I recently learned that the East Coast of the United States was home to a whole bunch of pirate towns. New York itself was a hotspot for piracy, and I spent a fair bit of time reading about it this week.

Before the United States was formed, the Atlantic coastline was a battleground for economic control. European empires, private merchants, and opportunistic outlaws vied for dominance over the lucrative trade routes between the Americas and Europe. Among the most feared economic disruptors were the pirates who patrolled the eastern seaboard, exploiting the chaotic governance of colonial territories. Their activities were not just acts of theft but part of a larger underground economy that shaped commerce, international trade, and even colonial policy.

The Golden Age of Piracy (1650s-1730s)

The height of piracy along the American coast coincided with the expansion of colonial trade. During the late 17th and early 18th centuries, pirates thrived in the weakly governed waters of the Caribbean and North America. The vast distances between colonies and slow communication made enforcement difficult, giving pirates free rein to seize goods, disrupt commerce, and engage in black-market trade.

One of the key economic drivers of piracy was the Triangle Trade, where goods, slaves, and raw materials moved between Europe, Africa, and the Americas. Pirates often targeted Spanish, British, and French merchant ships carrying gold, sugar, tobacco, and other high-value commodities. The plundered goods were then sold at deep discounts to colonial merchants who saw piracy as a cheaper alternative to paying high tariffs and import duties imposed by European powers.

Pirates as Economic Actors

Unlike the romanticized depictions of piracy in popular culture, many pirates functioned as part of an informal economic network. Some colonies, particularly those with weak enforcement, benefited directly from piracy. Port towns like Charleston, South Carolina, and Newport, Rhode Island, became thriving pirate hubs, with merchants and officials willing to overlook stolen goods in exchange for economic gain. In some cases, pirates reinvested their wealth into local economies, spending lavishly and financing the growth of colonial infrastructure.

Blackbeard (Edward Teach): Perhaps the most infamous pirate, Blackbeard terrorized the American coastline in the early 1700s. His blockade of Charleston in 1718 demonstrated how pirates could wield economic power over colonial cities.

The Pirate Republic of Nassau: From 1706 to 1718, the Bahamas, particularly Nassau, served as an unofficial pirate stronghold, where outlaws formed their own self-governed economy outside British control.

William Kidd: Initially hired as a privateer to hunt pirates, Kidd turned to piracy himself when he realized it was more profitable than legal maritime trade.

Government Responses and the Fall of Piracy

As piracy disrupted trade, European governments began cracking down on the practice. The British Crown, recognizing the economic cost of lost commerce, intensified anti-piracy efforts in the early 18th century. The 1717 Proclamation for Suppressing of Pirates offered full pardons to pirates who surrendered within a year, while those who refused faced execution.

Governors, once complicit in piracy, were forced to choose between economic convenience and the growing might of the British navy. Some, like Governor Alexander Spotswood of Virginia, aggressively pursued pirates, leading to the famous capture and killing of Blackbeard in 1718.

By the 1730s, piracy along the East Coast had largely been eradicated, replaced by more structured, government-controlled trade. However, the economic legacy of piracy remained—many merchants who had once profited from smuggling and illicit trade would later become leaders in the colonial resistance against British taxation, fueling early American revolutionary sentiment.

The Economic Legacy of Piracy

While pirates were ultimately hunted down, their impact on colonial economies was undeniable. Their role in bypassing British trade restrictions and fostering local economic independence helped shape the rebellious spirit of early American merchants. Some historians argue that the widespread acceptance of smuggling and illegal trade networks helped prepare the colonies for later defiance against British economic policies, such as the Navigation Acts and the Stamp Act.

In many ways, piracy was a symptom of an emerging free market at odds with the rigid mercantilist policies of European empires. The desire for economic freedom—ironically driven in part by pirate activity—would later manifest in the larger struggle for American independence.

Supporting Research:

Rediker, Marcus. Villains of All Nations: Atlantic Pirates in the Golden Age. Beacon Press, 2004.

Cordingly, David. Under the Black Flag: The Romance and the Reality of Life Among the Pirates. Random House, 1995.

Burgess, Douglas R. The Politics of Piracy: Crime and Civil Disobedience in Colonial America. University of New England Press, 2014.

British Proclamation of 1717, “Act for the More Effectual Suppression of Piracy.” London Gazette, 1717.

Woodard, Colin. The Republic of Pirates: Being the True and Surprising Story of the Caribbean Pirates and the Man Who Brought Them Down. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2007.

Literature review

Man vs. Machine: The Influence of AI Forecasts on Investor Beliefs

For years, financial analysts and investors have debated whether quantitative models, often considered “AI”, can reliably predict stock market movements. A new study explores this question, revealing that while AI-generated financial forecasts are sophisticated, they often struggle to gain investor trust. The research examines how different types of financial forecasts—AI-only, hybrid AI-human, and human-only—affect investor perceptions, credibility, and decision-making. The results suggest that investors remain deeply skeptical of AI-driven predictions, with the perceived credibility of AI-only forecasts dropping significantly compared to traditional human analysis (-0.257, p = 0.001). This means that, on average, AI predictions were rated much less trustworthy than human forecasts, with a confidence level of over 99%. Hybrid models that combined human expertise with AI performed slightly better (-0.135, p = 0.085), but they still didn’t reach the trust levels of human analysts.

One of the key findings was that AI literacy plays a significant role in shaping investor sentiment. Investors who were more knowledgeable about AI were actually less likely to trust AI-generated forecasts (-0.067, p = 0.030), likely because they understood the limitations of machine learning models in volatile financial environments. Interestingly, risk tolerance also influenced perceptions—investors willing to take on more risk were more accepting of AI-generated insights (0.075, p = 0.001). Political leanings factored in as well, with Democratic investors displaying stronger skepticism toward AI-only forecasts (-0.103, p = 0.004). When comparing AI models, traditional statistical approaches like Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) were rated the most credible (0.184, p = 0.001), while deep learning models and Bayesian techniques failed to gain much investor confidence. The study also found that financially literate investors updated their expectations more aggressively when confronted with AI predictions (0.304, p < 0.001), suggesting they were more willing to adjust their views but remained wary of blindly trusting machine-generated insights.

The implications of this study are clear: while AI has the potential to revolutionize financial forecasting, trust remains a major barrier to adoption. Hybrid AI-human models may be the best path forward, offering the benefits of automation while retaining the credibility of human expertise. Financial firms leveraging AI must recognize that simply offering data-driven insights is not enough—they need to consider investor psychology, transparency, and how forecasts are communicated. Without addressing these trust gaps, AI-driven financial predictions may struggle to gain widespread acceptance, no matter how advanced the underlying technology.