15 - Dividend discount models

This article is going to focus on the first method for figuring out what a stock is worth. You’ll want to look at the last article for some of the formulas that I’m using.

Also, I’m going to try something new going forward. I will be publishing a paid version of this article that will release right after this one. The article you’re reading now is designed for anyone interested in improving their personal finances, but the paid version is “professional”, designed for people who may want a bit more of the details on a topic like this. I have chosen the cheapest price possible for these paid versions, Substack literally won’t let me charge a lower price. I will keep all content that DIY investors need to manage their portfolio and save and build their net worth for the future free forever, but if you’re looking for a little more on top of that, check out the paid version. I am thankful for your time and attention, so the first two of the pro articles will be free to give you a sense of what will be included.

Key points:

We can discount future dividends to come up with a price today of what the stock is actually worth.

The dividend discount model is in some ways the most robust way of valuing stocks, but the model only works for companies that issue dividends.

To request a topic anonymously, fill out this form. To reach me with questions, please email alexwarfel@gmail.com. You can also reply to this email directly.

Picking up from my last article, lets talk through an actual model for valuing a stock. If the stock pays dividends1, we can value the company with the dividend discount model. When a company offers a dividend, it’s typically a very stable dividend because of signaling theory. Signaling theory is the idea that when a company takes a corporate action, investors will infer things from that action. For example, companies try not to cut their dividends because that would send a bad signal to Wall Street and investors which would then decrease the stock price probably more than is reasonable. Can you blame investors? Maybe the company cut the dividend because the future isn’t very bright for the company. This means that companies that offer dividends typically keep them and work hard not to cut them.

This means we can consider the dividends that companies offer as a kindof stable cash flow, which also means we can project out and then discount those future cash flows to come up with a value we think that the stock is worth today. This makes sense because those dividends are tangible cashflows that we earn as investors for just holding the stock. The simplest place to start is if we consider that the company pays this dividend forever. This is called a perpetuity and the value of this perpetuity is calculated in the following way:

We’ll end up using this formula more in depth later on, but for now we can start here. If the dividend is $2, then we would use $2 in the numerator. The discount rate has to be assumed and it’s related to how much we expect the future cash flows to happen and how valuable those future cash flows are. This is where we come to the Gordon Growth model. This model is still a perpetuity because it’s the value of next year’s dividends, however the discount rate in the denominator is actually the difference between the discount rate and how much the dividends are growing. You could think of the discount rate as something similar to inflation and the dividend growth rate as the rate of growth of the dividend. The difference between the two is the rate of actual value that you earn as time goes on. This is called putting things in “real” terms2.

This is a fundamental model in finance because of its simplicity. This model assumes that dividends grow in perpetuity (questionable) and that the cost of equity is greater than the growth rate expected for dividends, which may not always be true. Read more about that here. This is a good place to start though because you can get a little more specific. The below formula is a two stage dividend discount model. The first stage is a series of dividends (D), which is discounted and then eventually the first stage ends and the second stage is a singular value which is a perpetuity.

Notice how we’re discounting each of the dividends by a specific rate but then at the end we have to figure out a price. Well, analysts typically consider this a perpetuity because they know that a company is a going concern. This means that a company expected to stay in business in perpetuity. Once we calculate that perpetuity, we discount the value of that perpetuity back to today, and that gives us the value today of that perpetuity deep in the future. One problem with models like this is that that perpetuity bit at the end makes up most of the value, which doesn’t always make sense because we know companies don’t last forever, they typically last about 18 years.

Let’s say the company pays a $2 dividend. Here’s a table of what that would look like:

This was constructed using the following rates:

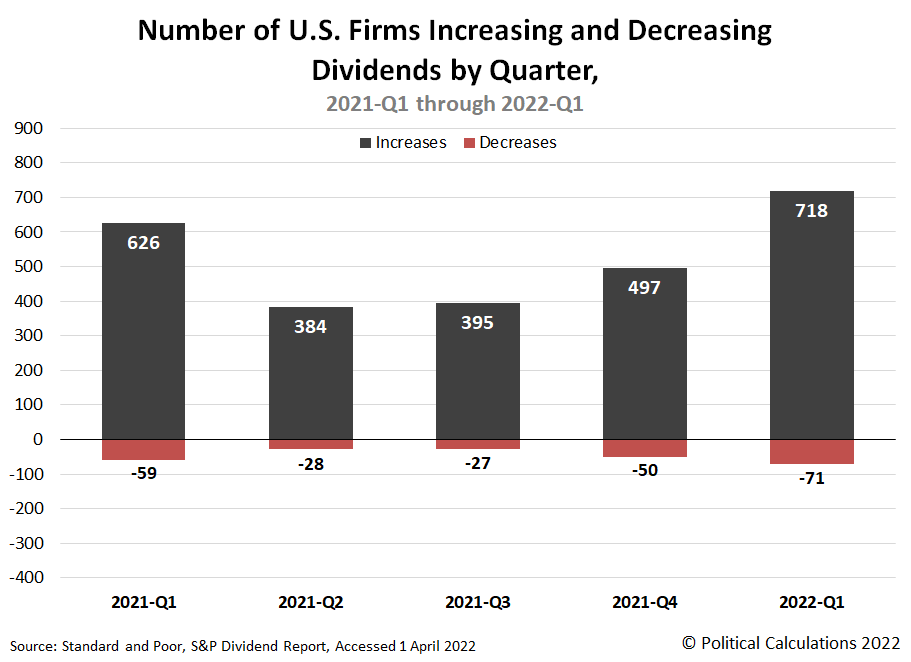

You can see the total on the bottom right indicates the stock is probably worth $127.21. The final stock price is calculated using the Gordon Growth model and then we sum all of the nominal values to get a sense of what we think the cash flow looks like. The drawback to this way of calculating a stock price is that a dividend is required, and not all stocks issue dividends. On the flipside, this could be considered the most robust model because we are only considering cash flows that are actually coming to investors. More companies are issuing more dividends, however:

The dividend discount model does oversimplify the investment decision, which can be a pro or a con depending on how you look at it. High growth stocks may not offer dividends either, which means they can’t be valued by this model. All things considered, this model is a good starting point.

Support

If you’ve enjoyed this article and you’d like to support me, please consider checking out some of the spreadsheets that I’ve built to make your financial planning easy. You can also subscribe to the paid version of this newsletter. Thank you!

A dividend is a payment made by a corporation to its shareholders, usually in the form of cash or additional shares. It's a way for companies to distribute a portion of their earnings back to their investors.

“Real” just means “after inflation”