4 - Valuations matter

But why?

Valuation matters. We talked about valuation multiples in a previous article. Valuations play a decently sized role in dictating future returns. This is because return is a function of the price you pay. This is clearer nowhere other than the bond market. Bonds are not very intuitive, so I’ll spend a moment describing how they work.

Key points:

Return is a function of price. The less you pay today correlates with the return over the next three and five years.

Valuation levels explain about 30% of expected future returns over the next three years, and about 45% of the returns over the next five years.

Bond pricing and equity pricing work similarly in that investors try to figure out what the future payout will be, and then work backwards from there. For bonds, these cash flows are contractual obligations unless special circumstances arise. Many bond valuations hinge on the likelihood a company will go bankrupt, referred to as credit risk. This is one of many risks that bond investors face though. Based on these contractually obligated future payments, people then barter over the price today of these bonds.

Imagine a situation where I offer to pay you $100 in a year. Well, having $100 a year from now is not preferable to having $100 right now, so there’s no way I’d pay $100 today for $100 in the future. But maybe you’d be willing to pay $90 today for $100 in the future. This means you’d make $10 (or 11.1%) in a year. If we put this bond on the market so that anyone could buy it, some people may think I’m likely to default and therefore not pay them back in a year. Maybe they would only be willing to pay $80 for that $100 payout in the future because they need $20 to entice them into this “risky” transaction. But other investors could look around and see that most other bonds are only returning about 5% per year, so investing in my bond at $90 sounds like a great deal. These two groups trade back and forth and so the price will fluctuate around $90, maybe up to $95, and maybe down to $85. This “rate that you can get elsewhere” is heavily impacted by the Federal Reserve which essentially sets the lowest, but safest interest rate for the whole economy. My bond carries more risk than the US government because the US is less likely to default and therefore more likely to pay people back in a year. This means that my bond should never trade in such a way that you can make more money investing in the US government than through my bond.

This is what I mean when I say that returns are a function of the price you pay. The reason we don’t think about things this way for equities is because no one is sure what the future payments will be. You’re buying ownership of a company, but you have no idea if that company will be successful a year or two from now.

- Source

This is one reason that equities are so volatile. It could be $100 in a year, it could be $80, or it could be $200, depending on the success of the company. When investing, the first thing sophisticated investors tend to do is make an educated guess at how much that future payout is going to be, and then work backwards to figure out how much to pay today for that future cash. To illustrate this point, here’s some data I put together using the cyclically adjusted price to earnings ratio and returns of the S&P 500, called the CAPE ratio. Reminder: this is how many dollars investors are willing to pay today for one dollar of earnings.

We’re comparing the Willshire 5000 total return index to the cyclically adjusted price to earnings ratio, often called the CAPE ratio (we assume dividend reinvestment for both). The CAPE ratio earnings in the denominator is calculated by taking the average inflation-adjusted earnings over the last 10 years for S&P 500 companies, and then they compare it to the S&P 500 total return index. Is it fair to compare the Willshire 5000 to the S&P 500? Not exactly, because the S&P 500 is made up of the largest companies by market cap in the United States. The Willshire 5000 tracks the performance of the whole U.S. stock market, and for what it’s worth, tracks significantly fewer than 5,000 companies listed on it. In 1998, the number of companies was around 7,500, but the number recently fell to 3,687 as of 12/31/21. In any case, these differences should be minor enough for us to explore the relationship between valuation and future returns.

You can see above that when the price to earnings ratio is high, annualized returns over the next 3 years tend to be low. Based on this simple regression, we can see that the valuation multiple explains about 30% of the annualized returns over the next 3 years. This relationship grows stronger though, if we consider the return over the next 5 years.

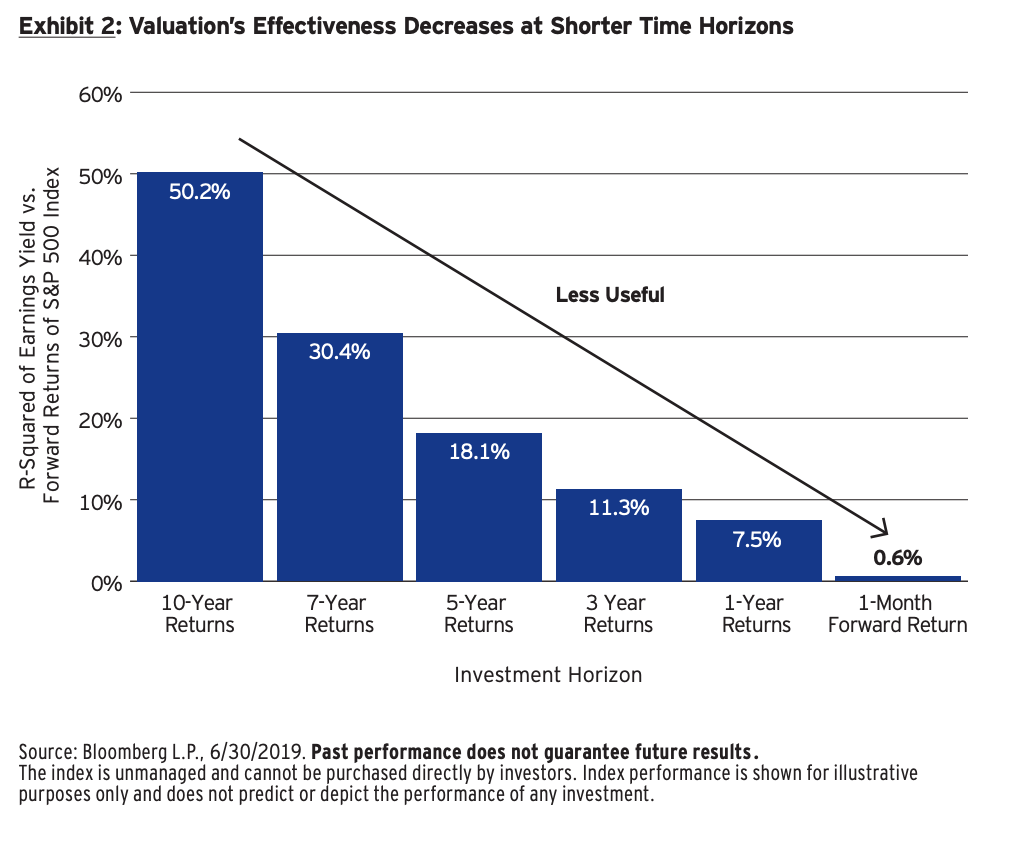

Here we can see the valuation multiple explains 45% of the returns over the next 5 years. This is supported in other empirical research. For example, Invesco found that valuations play a smaller role in dictating future returns as the investment horizon (or time you expect to hold the stock) declines.

This all points to the idea that it’s important not to overpay for your equity. When you do, returns suffer.