The Fed, Tariffs, and Overpriced Stocks—What’s Next for Markets?

History Is Repeating Itself—And It’s Not Good News for Overpriced Stocks.

Today’s article takes 13 minutes to read.

Key Takeaways

In the news: Stocks Are Overvalued - The equity risk premium turned negative for the first time since 2002, meaning investors are being compensated less for taking on stock market risk, signaling potential trouble ahead. Despite warning signs, individual investors poured a record $62.5 billion into stocks in December, continuing to chase big tech and AI-driven optimism.

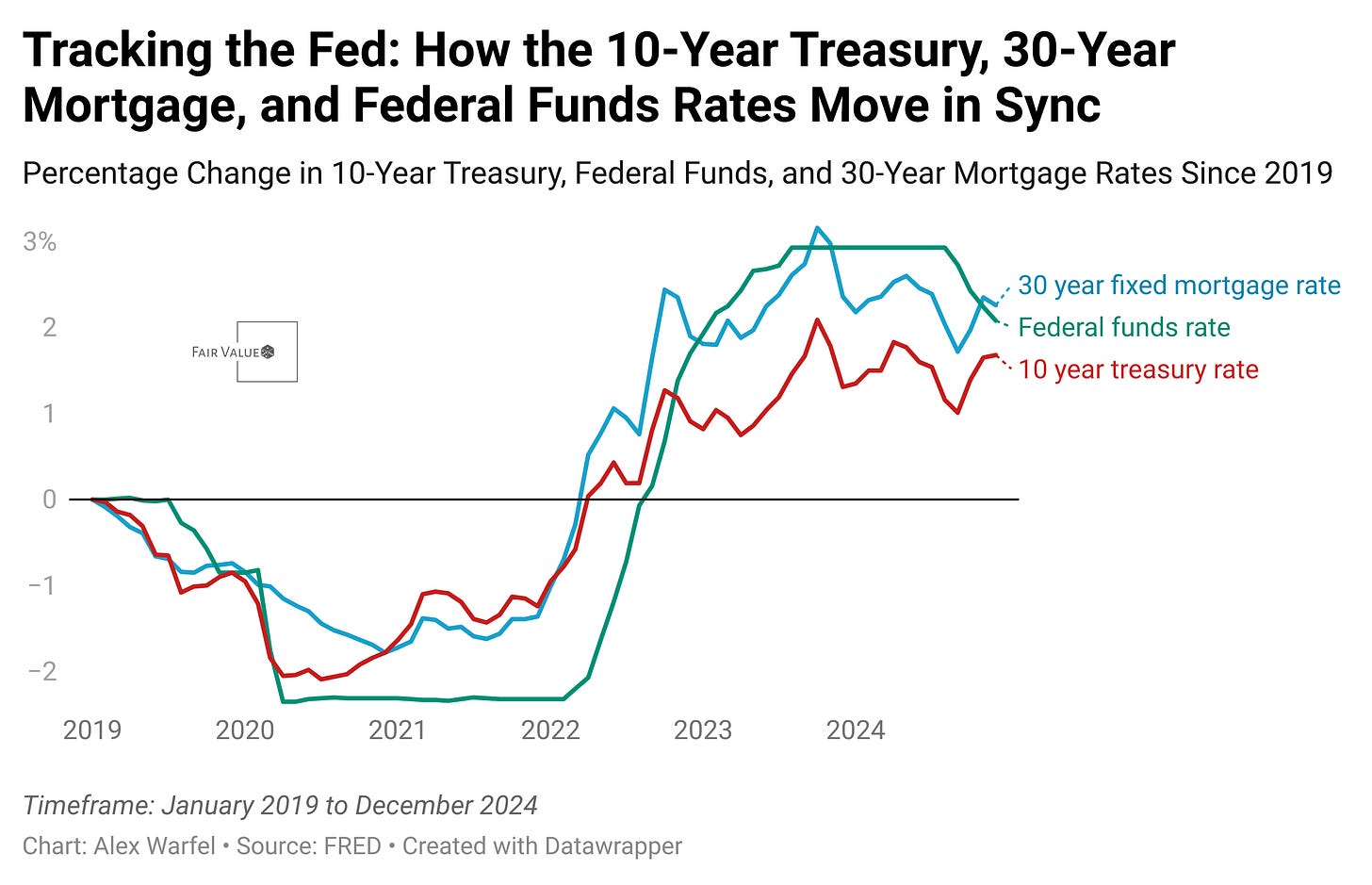

Chart of the week: Interest Rates Are Highly Connected - The federal funds rate influences Treasury yields and mortgage rates, meaning Fed policy decisions directly impact borrowing costs for homebuyers and businesses.

Beyond bias: Recency Bias Skews Decisions - Investors often overreact to recent market trends, assuming current conditions will continue indefinitely, leading to poor decision-making during market highs and lows.

Building wealth: Reverse Budgeting - A reverse budget prioritizes savings first by automatically setting aside money before spending, helping individuals build wealth effortlessly. This method leverages behavioral finance principles like paying yourself first and mental accounting, reducing the temptation to overspend while fostering long-term financial security.

Historical perspective: The McKinley Tariff’s Lessons on Trade - The 1890 tariff aimed to protect U.S. industries but led to higher consumer prices, strained global trade, and political backlash—similar to modern tariff policies under Trump and Biden.

Literature review: ESG Investing is Driven by Psychology - Behavioral finance research shows ESG investing is fueled more by emotions, branding, and social values than by clear financial benefits, making it vulnerable to hype and shifting trends.

In the news

I am not going to talk about DeepSeek because that topic has enough coverage everywhere else. Instead, I want to talk about something important that I saw for the broader stock market.

Stocks are looking increasingly expensive, and a key valuation metric signals trouble ahead. The equity risk premium, which measures how much extra return investors get for owning stocks instead of safer government bonds, turned negative in late December for the first time since 2002. This means that stocks, relative to bonds, are offering less compensation for their added risk than they have in decades. With the S&P 500’s earnings yield falling below 10-year Treasury yields, the market is showing signs of extreme valuation—raising concerns that investors are paying too much for stocks despite the risks.

Despite this, demand for stocks remains strong, fueled by individual investors pouring $62.5 billion into equity funds in December—the highest monthly inflow on record. Many investors continue betting on big tech, encouraged by past gains and AI-driven optimism. However, historically, negative equity risk premiums have preceded market pullbacks. The last time this happened was during the early 2000s, following the dot-com bubble, which eventually led to a significant market correction.

What This Means for Investors

High valuations and a negative risk premium suggest caution. Relying solely on past returns to justify stock prices is dangerous—when risk isn’t properly rewarded, stocks become vulnerable to declines.

How to Prepare

Diversify Beyond Stocks – With bonds yielding competitive returns, consider reallocating some funds into fixed income to reduce risk.

Focus on Value, Not Hype – Expensive stocks like Nvidia and Tesla may look strong, but past gains don’t guarantee future performance. Look for companies with strong fundamentals and sustainable growth.

While nobody can predict the exact timing of a pullback, the current market setup looks eerily similar to past moments of overvaluation. Investors who ignore these signals may find themselves caught off guard when the tide turns.

Chart of the week

The federal funds rate is the interest rate set by the Federal Reserve that banks use to lend money to each other overnight. This is the rate the news often quotes when we discuss the Fed. This rate influences nearly every other interest rate in the economy, including Treasury yields and mortgage rates. It’s often considered the “floor” of interest rates in the United States. When the Fed raises rates to control inflation, borrowing money becomes more expensive, slowing down economic activity. One key connection is with the 10-year Treasury yield, which represents the return investors expect from holding U.S. government bonds for a decade. Since Treasurys are considered low-risk, their yield reflects investor expectations for future interest rates and inflation. When the federal funds rate rises, it often pushes Treasury yields higher as investors demand better returns to compensate for the higher cost of borrowing.

The 30-year fixed mortgage rate closely follows the 10-year Treasury yield because banks and lenders use it as a benchmark for setting mortgage rates. When Treasury yields rise, mortgage rates tend to go up, making home loans more expensive. This is why Fed decisions on interest rates have a big impact on the housing market—higher rates can cool down demand by making mortgages less affordable. Understanding this relationship is crucial because it helps people predict when borrowing costs might rise or fall. Whether you’re looking to buy a home, refinance a loan, or invest, watching these interest rates can give you an edge in planning major financial decisions. Lately, the Federal Funds rate has gone down, but 10 year treasuries and mortgage rates have popped up. This signals that investors expect more inflation in the future.

Beyond bias

Recency bias is the tendency to place too much weight on recent events while ignoring long-term trends. In personal finance, this often leads investors to assume that whatever is happening now will continue indefinitely. For example, after a strong stock market rally, people may become overconfident and believe stocks will keep rising, causing them to take on too much risk. On the flip side, during a market downturn, investors might panic and assume the losses will never stop, leading them to sell at the worst possible time. This bias explains why many investors sell low and buy high, the opposite of a successful investment strategy (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979).

To counteract recency bias, it’s essential to take a long-term perspective. Instead of making investment decisions based on short-term market movements, focus on historical trends and fundamental data. For example, while stocks may drop sharply in a recession, history shows that markets tend to recover over time (S&P Dow Jones Indices). Setting rules, such as rebalancing your portfolio periodically or following a well-defined investment strategy, can help prevent emotional decision-making. Additionally, reviewing past market cycles and understanding how different assets perform over time can provide reassurance and prevent impulsive reactions to recent events.

Building wealth

A reverse budget flips the traditional budgeting method on its head by prioritizing savings first, rather than tracking and limiting spending across multiple categories. Instead of allocating money for expenses and seeing what’s left to save, a reverse budget has you decide on a set savings goal—such as 20% of your income—before spending on anything else. This method is sometimes called paying yourself first, which is a principle endorsed by financial experts like David Bach, author of The Automatic Millionaire. Research suggests that automating savings leads to better financial outcomes, as people are less likely to spend money they never see in their checking account (Thaler & Sunstein, Nudge, 2008). By setting up automatic transfers to a retirement account, high-yield savings, or investments, individuals remove the temptation to spend impulsively, making it easier to stay on track with long-term goals.

The psychology behind a reverse budget aligns with behavioral finance theories, particularly the concept of mental accounting, introduced by economist Richard Thaler. People tend to separate their money into different “buckets” mentally, and when savings are removed from immediate access, they are far less likely to dip into them (Thaler, Misbehaving, 2015). A reverse budget helps individuals feel more in control of their finances without the stress of tracking every dollar. It also reduces decision fatigue, since savings are automated, leaving only discretionary spending to manage. This approach is particularly effective for people who struggle with traditional budgeting methods or feel overwhelmed by detailed expense tracking. By focusing on long-term financial security first, a reverse budget encourages disciplined spending habits, prevents lifestyle inflation, and makes wealth-building a more natural part of financial decision-making.

Product focus

Take control of your financial future with Rainier FM—your AI-powered financial planning companion. FM stands for Financial Model, and that’s exactly what this app delivers: optimized, data-driven financial plans tailored to your goals. Using advanced optimization techniques and AI-driven insights, Rainier FM helps users navigate everything from retirement planning to wealth building with confidence. Pricing reflects the cost of running the service, but I’m actively gathering feedback to refine and improve it. If this sounds like something you’d find valuable, feel free to reach out or sign up—I’d love to hear what you think as I continue developing the platform!

Historical perspective: The McKinley Tariff and Its Impact on Trade

Today, we’re going to talk about tariff’s because they are in the news. Specifically, Trump has referenced McKinley as an example of successful tariffs. Here is the full story. In 1890, the United States passed one of the most significant tariff laws in its history: the McKinley Tariff. Named after Congressman William McKinley, who later became the 25th president of the U.S., this law dramatically raised import taxes on foreign goods. It increased tariffs on certain imports to nearly 50%, one of the highest rates ever seen in the country. The goal was to protect American industries from foreign competition, particularly manufacturers and farmers producing goods like wool, sugar, and tinplate (U.S. House of Representatives, 1890). However, while the tariff was meant to help American businesses, it also had unintended consequences that hurt consumers and farmers.

At the time, tariffs were a major source of government revenue, since there was no federal income tax yet. Supporters of the McKinley Tariff believed it would make American-made goods more competitive by making foreign products more expensive. However, opponents—especially farmers—argued that higher tariffs led to increased costs for imported goods, including tools and materials needed for agriculture. Many Americans saw prices on everyday items rise, making life harder for working-class families (Taussig, 1892).

The tariff also strained U.S. relations with foreign countries, particularly European nations that relied on selling goods to America. In response, some of these countries placed their own retaliatory tariffs on American exports, making it harder for U.S. farmers to sell their crops overseas. One major impact was the decline in American agricultural exports, which caused hardship in rural areas. Many farmers, especially in the Midwest, blamed the McKinley Tariff for their financial struggles and turned against McKinley’s political party, the Republicans, in the next elections (Stanwood, 1903).

By 1894, public backlash against the McKinley Tariff led to a major political shift. The Democrats won control of Congress, and the new administration under President Grover Cleveland quickly passed the Wilson-Gorman Tariff Act, which lowered many of the McKinley Tariff’s rates. However, this did not completely undo the economic effects, as international trade relations had already been damaged. The McKinley Tariff remains a historical example of how trade policies can have widespread economic and political consequences, shaping elections, industries, and international relationships for years to come (Irwin, 2017).

In recent years, both the Trump and Biden administrations have utilized tariffs as tools to influence trade policy. During his tenure, President Trump imposed tariffs on various imports, including steel and aluminum, aiming to protect domestic industries and address trade imbalances. These actions led to trade tensions with countries like China, Canada, and Mexico. The Biden administration has maintained some of these tariffs and, in certain instances, increased them. For example, in May 2024, tariffs on Chinese-made solar cells and electric vehicle batteries were raised. These measures reflect a continued strategy of using tariffs to address trade concerns and support domestic industries.

Supporting research:

• Irwin, Douglas A. Clashing Over Commerce: A History of US Trade Policy. University of Chicago Press, 2017.

• Stanwood, Edward. American Tariff Controversies in the Nineteenth Century. Houghton Mifflin, 1903.

• Taussig, Frank William. The Tariff History of the United States. G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1892.

• U.S. House of Representatives. The Tariff Act of 1890 (McKinley Tariff). U.S. Government Printing Office, 1890.

Literature review

In this study, Professor Shefrin of Santa Clara University, the Leavey School of Business, explains why investing in ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) funds is mostly about psychology rather than just cold, hard numbers. He shows how emotions, personal values, and marketing play a huge role in why people pick “green” or “socially responsible” investments. Traditional finance theory says we invest to make money, but ESG adds an extra layer: people want their investments to reflect their personal beliefs—even if that might mean earning slightly less in returns.

One of the paper’s main examples compares ESG-investing to buying either “white eggs” or “brown eggs.” White eggs stand for companies that do good things like helping the environment or treating workers well, while brown eggs stand for regular companies that don’t emphasize these goals. Some investors strongly prefer white eggs because it feels right to them, while others don’t really care. Whether white eggs cost more depends on how many people want them. If demand is high enough, white eggs (ESG stocks) might become more expensive, meaning investors get a smaller profit. But if there aren’t enough buyers, white eggs and brown eggs might cost about the same, so there might be no penalty for choosing the ESG option.

The paper also looks at how companies selling ESG products use marketing to appeal to people’s emotions. Many big investment firms, like Morgan Stanley or BlackRock, make their ESG funds seem exciting, impactful, and possibly more profitable than they really are. For instance, they’ll sometimes point to short-term data showing ESG stocks doing just as well as regular stocks. But at other times—like in 2022 and 2023—some ESG investments dropped much more than standard market indexes. Professor Shefrin shows how advertising and branding can lead people to overestimate both their future returns and the good their money is doing for society.

Another interesting finding is that ESG enthusiasm can swing up or down like a trend or a fad. When more people get excited about doing good for the planet, they might rush to buy green energy stocks, raising prices. But if interest rates climb or people start to lose faith, those same stocks can fall hard. For example, from early 2023 to early 2024, a major clean energy index went down by about 31%, while global stocks rose by 27%. This big difference suggests that emotions and hype strongly affect prices.

Finally, Shefrin argues that we need clearer rules and better information for ESG-investing. Because there’s so much confusion about which companies are truly “green,” investors can be misled by marketing claims. He suggests we treat ESG funds somewhat like consumer products: we should look at branding and labeling closely, and be aware of how ads or “green” promises could trick us into paying more than something is worth. By making things less confusing—through clearer ratings, stricter oversight, and honest communication—people can still invest in a way that reflects their values, but with a clearer idea of the costs and risks.

Overall, the paper shows that ESG-investing combines money decisions with moral values and clever marketing. People care about more than profits alone: they also care about how those profits are made. However, it’s easy to be influenced by hype or branding, so Shefrin encourages investors to look past labels and examine the real-world impact of their investments—and to remember that markets can shift quickly when moods or beliefs change.