The Faster Race

How Inflation Changes the Rules of Economic Competition

When people talk about inflation, they almost always talk about prices. Gas costs more. Groceries cost more. Housing costs more. That’s real, and it matters. But it’s only half the story.

The part that gets less attention is what inflation does to the speed of economic life. Inflation doesn’t just make things more expensive. It makes the race faster. Every participant in the economy has to move quicker, decide sooner, and adapt more aggressively just to stay in place. And the people who were already moving fast pull further ahead.

I want to work through this idea, because I think it changes how you should think about your career, your savings, and your investments during periods of elevated inflation, which I’ll define here as CPI-U running above 3% year-over-year for at least six months.

The Generic Take (And What It Misses)

Most inflation commentary follows a familiar script. Prices are rising. The Fed will raise rates to cool things down. In the meantime, buy TIPS, own some real estate, and don’t hold too much cash.

That advice isn’t wrong. But it treats inflation as a price problem with an investment-allocation solution. It skips the mechanism underneath.

Inflation does more than raise the cost of goods. I’d argue it also compresses decision timelines, increases the penalty for inaction, and amplifies the gap between those who can adapt and those who can’t. That’s a framework, not an empirical law, but I think it’s a useful lens.

Think of it this way. In a low-inflation world, you can afford to wait. You can sit in a job that underpays you by 5% without feeling it much. You can keep your emergency fund in a savings account earning close to nothing. You can delay a move, skip a negotiation, or put off optimizing your portfolio. The cost of inaction is small.

In a high-inflation world, all of those costs compound faster. If your employer adjusts pay once a year and inflation is running at 4%, that 5% gap to market rates widens in real terms with every month you wait, because your purchasing power is falling while market wages keep moving. If your savings yield is below the inflation rate, your emergency fund isn’t just sitting still. It’s shrinking in real terms every month. The longer you wait to act, the more ground you lose. Inflation turns inaction from a minor drag into an active penalty.

The Race-Speed Framework

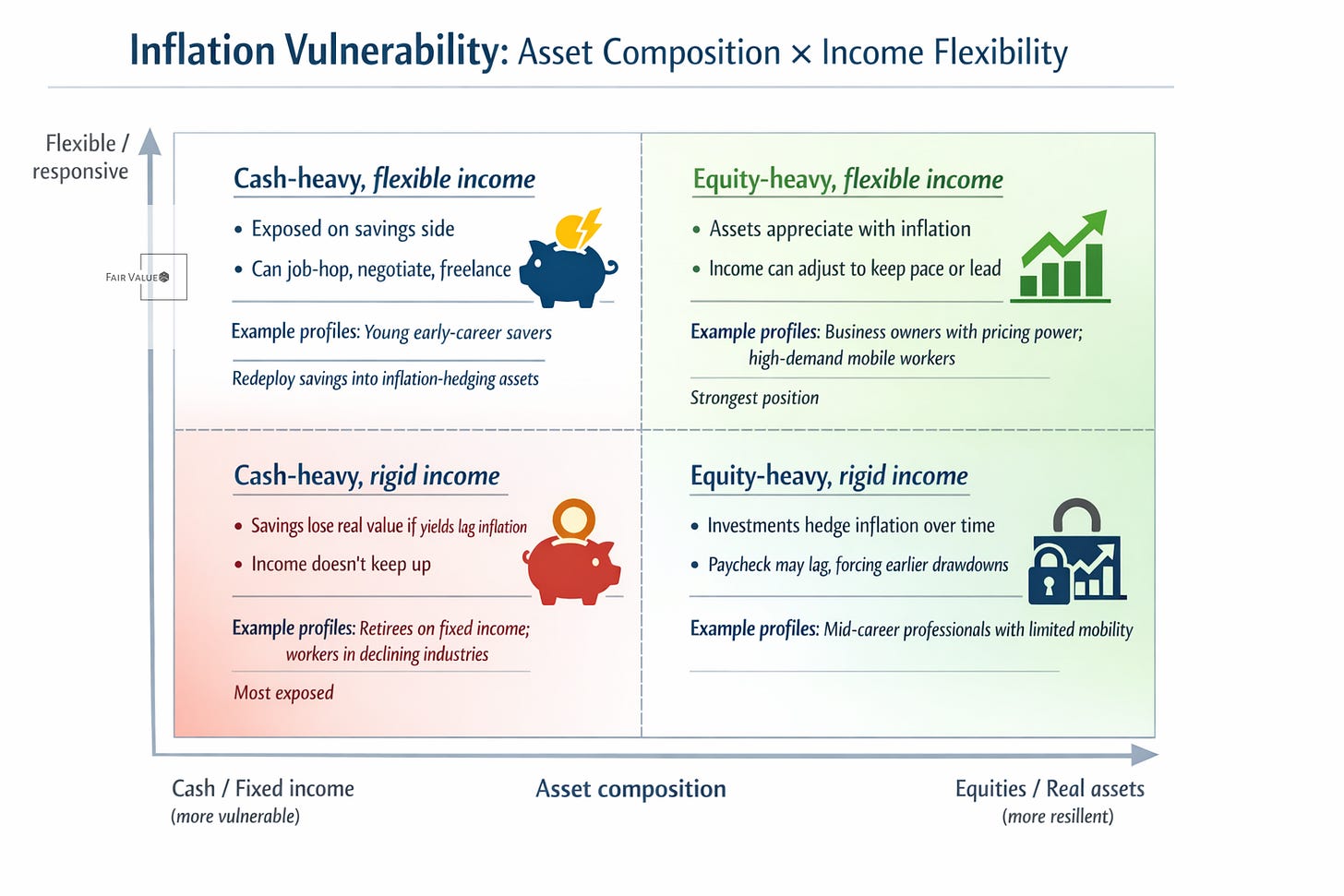

To make this concrete, I think about inflation vulnerability along two dimensions.

Dimension one is asset composition. Are your savings mostly in cash and fixed-income instruments, or in equities and real assets that tend to grow with (or ahead of) inflation?

Dimension two is income flexibility. Is your income rigid and slow to adjust (salaried with infrequent raises, fixed-income dependent, or in a field with limited mobility), or is it flexible and responsive (you can switch jobs, negotiate, freelance, or capture new opportunities)?

These two dimensions create four positions.

Cash-heavy, rigid income. This is the most exposed position in an inflationary environment. Your savings are losing real value (assuming yields lag inflation), and your income isn’t keeping up. Retirees on fixed income with money in savings accounts sit here. So do workers in declining industries who haven’t renegotiated in years. Inflation erodes from both sides.

Cash-heavy, flexible income. You’re exposed on the savings side, but you have a lever to pull. You can job-hop for a raise, negotiate harder, or take on side work. If you’re young and early-career with most of your savings in cash, this is probably you. The fix is straightforward. Redeploy savings into assets that keep pace. But the window to act narrows as inflation persists.

Equity-heavy, rigid income. Your investments are working for you, but your paycheck isn’t. This often describes mid-career professionals with solid 401(k) balances but limited job mobility, whether because of specialization, geography, or life constraints. The portfolio hedges inflation over time, but if your income falls behind, you might be forced to draw down savings earlier than planned.

Equity-heavy, flexible income. This is the strongest position. Your assets appreciate with inflation, and you can adjust your income to keep pace or get ahead. Mobile professionals with diversified portfolios, business owners with pricing power, and high-demand workers in growing fields tend to land here.

The framework isn’t about judging anyone’s position. It’s about making the tradeoffs visible. When inflation is low, the difference between these quadrants barely matters. When inflation runs hot, the gaps widen fast.

The Job-Switching Accelerator

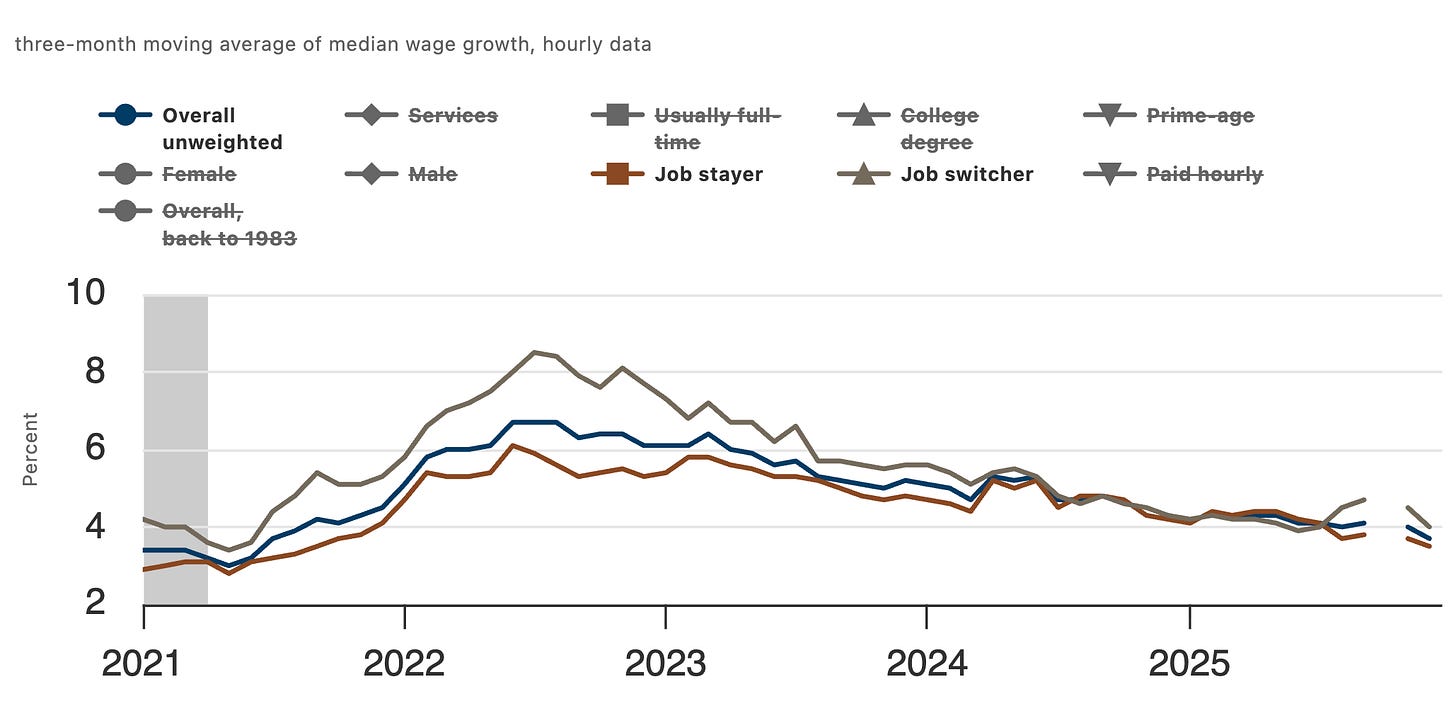

One place this dynamic shows up clearly is the labor market. During the 2021-2022 inflation spike, the wage growth premium for job switchers over job stayers widened significantly. The Atlanta Fed Wage Growth Tracker shows that median wage growth for job switchers peaked above 8% in mid-2022, while job stayers tracked closer to 5-6%, a gap much wider than the roughly 1 percentage point spread typical of the pre-pandemic years (2015-2019).[1]

The logic is straightforward. When prices are rising quickly, companies compete harder for talent. New offers reflect current market rates. But existing salaries often lag, because a large share of employers adjust pay on an annual cycle (a 2024 WorldatWork survey found roughly half of organizations do so),[2] and raises rarely match inflation in real time. The result is a growing gap between what you earn by staying and what you could earn by moving.

This creates a kind of musical chairs effect. Inflation makes staying in your seat progressively more costly. Switching gives you a reset to market rates, but it comes with risk. New environment, probation period, loss of tenure and institutional knowledge. The faster inflation runs, the more the math favors moving, and the more concentrated wage gains become among mobile, high-demand workers, while a larger group of stayers falls behind in real terms.

The Cash Paradox

The cash side is the hardest part to internalize. Cash feels safe during uncertain times. When markets are volatile and headlines are scary, the instinct is to hold more of it. But when savings yields fall below the inflation rate, cash turns from a safety net into a slow leak. (This isn't always the case. As of early 2026, top high-yield savings accounts offer around 4-5% APY[3] while CPI-U is running at roughly 2.7% year-over-year,[4] meaning well-placed cash can be roughly flat or positive in real terms. But during periods when inflation outpaces available yields, the erosion is real and persistent.)

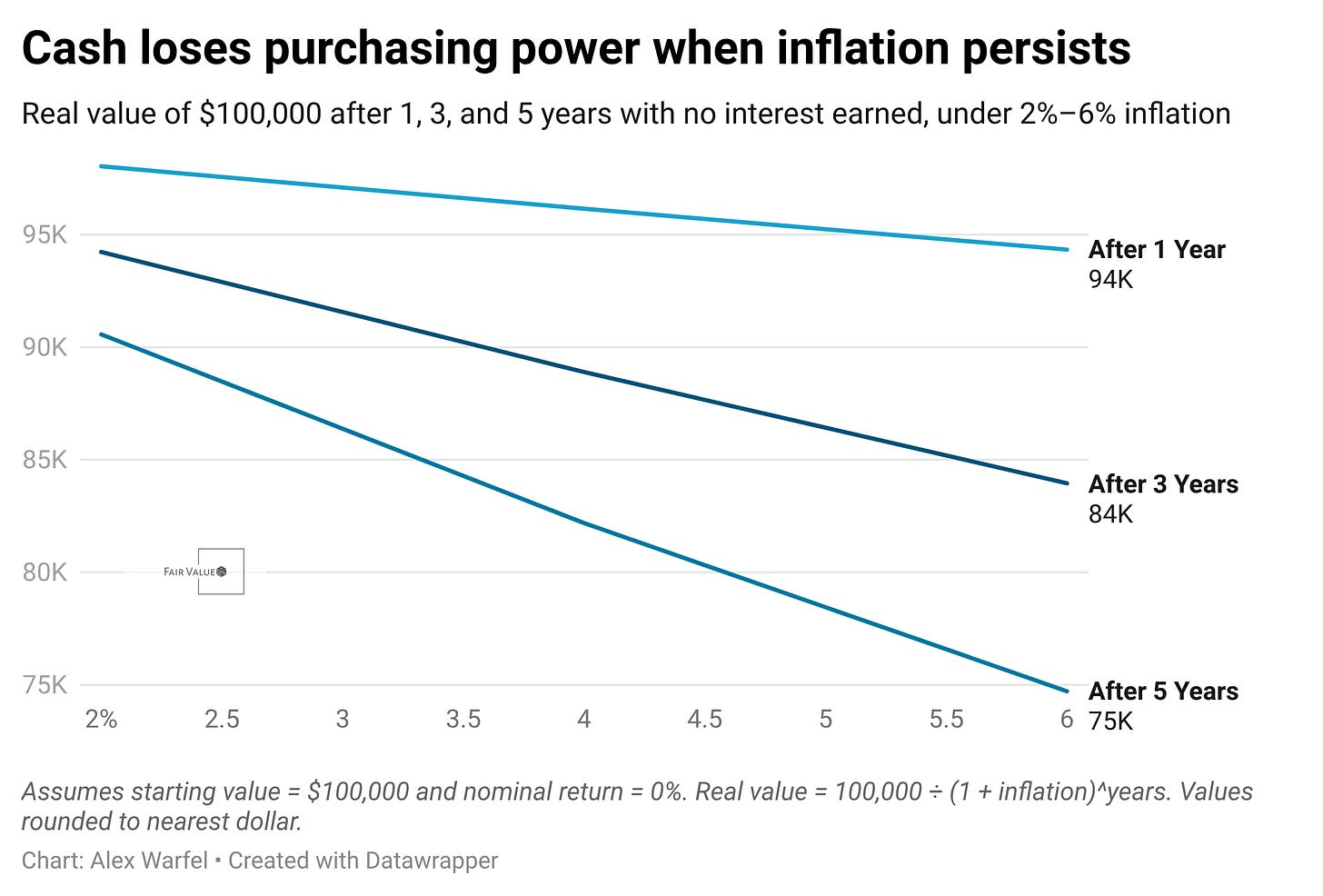

To see how this works, assume $100,000 earning no interest, eroded by compound inflation (real value = nominal / (1 + inflation rate)^years)[2]. At 3% annual inflation, that $100,000 loses about $2,900 in purchasing power the first year. At 5%, about $4,800. Over five years of 4% average inflation, you’ve lost nearly 18% of your real purchasing power (1 / 1.04^5 = 0.822, or a 17.8% loss).

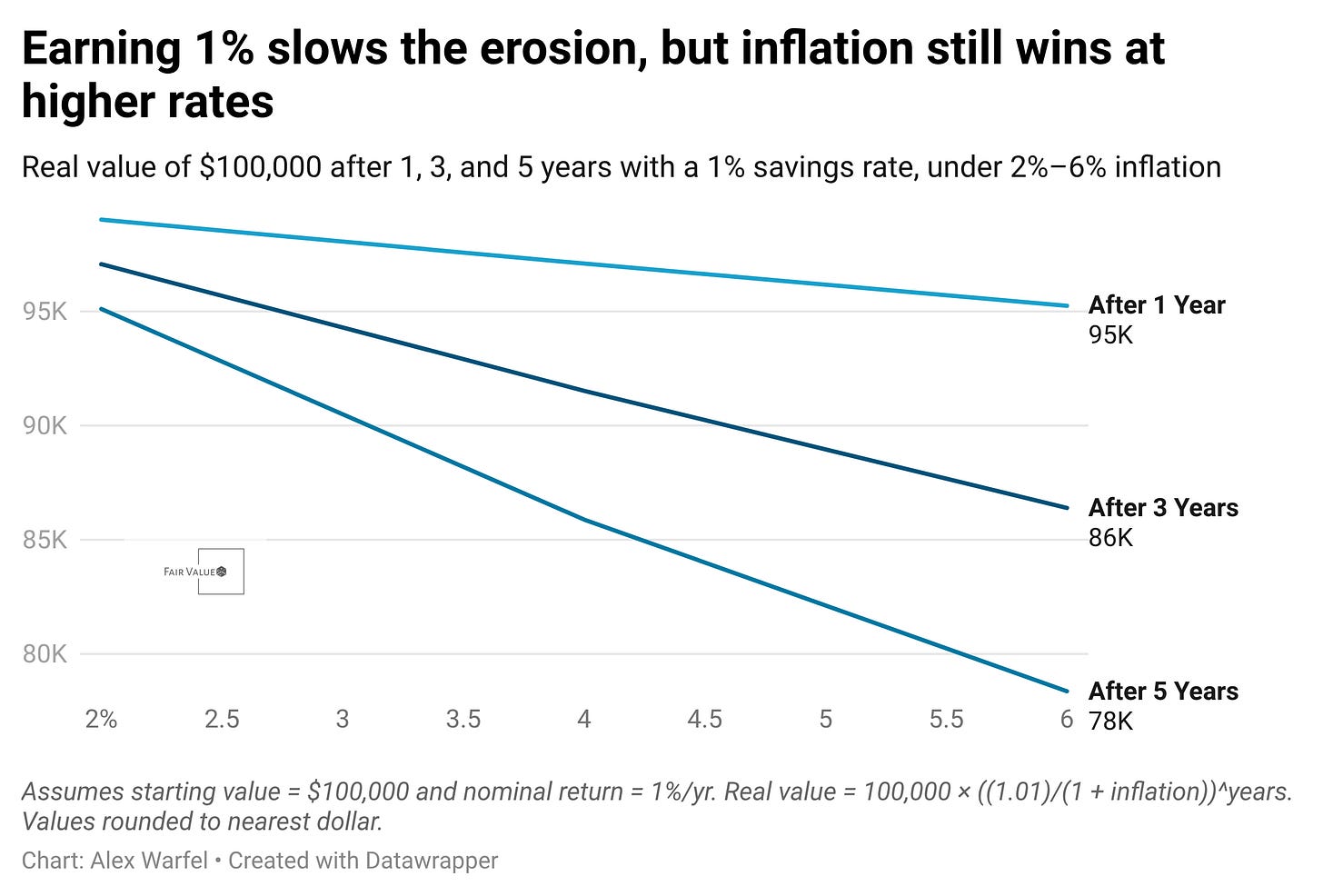

In practice, your savings earn some yield. The table below shows two scenarios: zero interest (worst case) and a 1% savings rate (a rough proxy for a basic savings account, though high-yield accounts currently offer much more).

If your savings yield exceeds the inflation rate, you’re gaining real purchasing power. That’s the case for some savers today. But in prior inflationary episodes (think 2021-2022, when CPI-U peaked above 9% while most savings accounts paid under 1%), the erosion was severe.

Meanwhile, equities have historically outpaced inflation over long periods. Using Ibbotson/SBBI data, US large-cap stocks delivered approximately 7.3% in real annualized returns from January 1926 through December 2024.[5] The problem is that “long periods” is doing a lot of work in that sentence.

The Timing Trap

Inflation gets genuinely tricky here, and simple advice falls short.

Equities are a strong long-term inflation hedge. Over decades, corporate earnings and stock prices tend to grow faster than the price level. But in the short term, rising inflation can hurt stocks, and has done so in several notable episodes.

When inflation picks up, interest rates typically follow, either because the Fed acts or because the market demands higher yields. Higher rates increase the discount rate applied to future cash flows, which means future earnings are worth less in today’s terms. Growth stocks with earnings far in the future get hit hardest. This is “duration sensitivity,” the same concept that makes long-duration bonds fall when rates rise.

So the asset class that protects you from inflation over a decade can punish you over a quarter. That creates a real dilemma. If you move from cash to equities during a period of rising inflation, you might suffer short-term losses even though you’re making the right long-term move. And if that shakes your conviction and you sell back to cash, you lock in both the drawdown and the ongoing inflation erosion.

The answer isn't to avoid equities. It's to understand that the timing of inflation hedging matters, and that the emotional experience of doing the right thing can feel terrible for a while.

What This Means in Practice

If I had to distill this into actionable takeaways, the Race-Speed Framework points to a few moves.

Audit your quadrant. Look at your savings composition and your income flexibility honestly. If you’re cash-heavy and income-rigid, inflation is working against you on two fronts. That’s worth addressing, even incrementally.

Don’t confuse safety with inaction. Cash feels safe, but when yields fall below inflation, its real value declines. At minimum, consider higher-yield alternatives for money you won’t need in the next 6 to 12 months. As of early 2026, top high-yield savings accounts offer roughly 4-5% APY[3:1] and 3-month Treasury bills yield in the high-3% range,[6] both above current CPI-U of approximately 2.7% (December 2025).[4:1] That math can shift quickly if inflation re-accelerates.

Watch the job-switching premium. If you’re in a field where market rates are rising faster than your employer adjusts, the cost of loyalty is measurable. That doesn’t mean you should switch reflexively, but you should know what you’re giving up.

Prepare for the timing trap. If you’re shifting from cash into equities, understand that you may experience short-term losses even if the long-term math is favorable. The conviction to hold through that is the actual investment skill, and it’s worth developing before you need it.

Your personal inflation rate is not CPI. National inflation is an average. Your experience depends on what you buy, where you live, and how your income adjusts. The framework works best when you use your own numbers, not the headline figure.

The Bigger Picture

Right now, there are reasons to think about inflationary pressure. The AI capex boom is massive: Alphabet guided $75B in 2025 capex and signaled a sharp increase to $75-$85B or more in 2026[7]. Amazon projected approximately $200B in 2026 capital spending[8]. Meta guided $60-$65B for 2025 and $115-$135B for 2026[9] and Microsoft’s quarterly capex has been running above $20B[10]. That spending is flowing into the real economy in the form of construction, land, equipment, and labor demand, though the exact magnitude of those downstream effects is difficult to measure in real time. Whether that spending eventually produces enough productivity gains to be disinflationary is the trillion-dollar question, and the honest answer is that nobody knows.

What we do know is that large-scale capex tends to create winners and losers before the productivity benefits (if they come) arrive. The spending hits first. The efficiency gains come later. Maybe.

If you’re sitting in cash waiting for clarity, inflation is the price of that patience. And the more inflation picks up, the faster the race gets.

This is general education and analysis, not personalized investment advice. Do your own research and consult a qualified professional before making investment decisions.

Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta. “Wage Growth Tracker.” https://www.atlantafed.org/chcs/wage-growth-tracker.

WorldatWork. “Report: 2024 Salary Increases Lower Than Projected.” Workspan Daily, May 7, 2024. https://worldatwork.org/publications/workspan-daily/report-2024-salary-increases-lower-than-projected.

Bankrate. “Best High-Yield Savings Accounts of February 2026.” https://www.bankrate.com/banking/savings/best-high-yield-interests-savings-accounts/.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Consumer Price Index Summary (December 2025).” BLS, January 13, 2026. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/cpi.nr0.htm.

Lamont, Duncan. “Scared of Investing As Stocks Hit All-Time Highs? Don’t Be.” Hartford Funds (whitepaper), August 29, 2025. https://www.hartfordfunds.com/dam/en/docs/pub/whitepapers/WP849.pdf.

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. “Market Yield on U.S. Treasury Securities at 3-Month Constant Maturity (DGS3MO).” FRED. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/DGS3MO.

Saba, Ismail. “Alphabet forecasts sharp surge in 2026 capital spending.” Reuters, February 4, 2026.

Prasad, Ananya Mariam Rajesh. “Amazon projects $200 billion capital spending this year.” Reuters, February 5, 2026.

Hu, Krystal. “Meta boosts annual capex sharply on superintelligence push.” Reuters, January 28, 2026.

Hu, Krystal. “Microsoft capital spending jumps…” Reuters, January 28, 2026.