Navigating Tariffs, Superstitions, and the First-Ever Bond Default

Why this market downturn is historic, how mutual fund managers’ zodiac years influence their decisions, and lessons from ancient Athens on debt crises.

Programming note: I’m skipping the news this week. It’s been a long week.

Key Takeaways

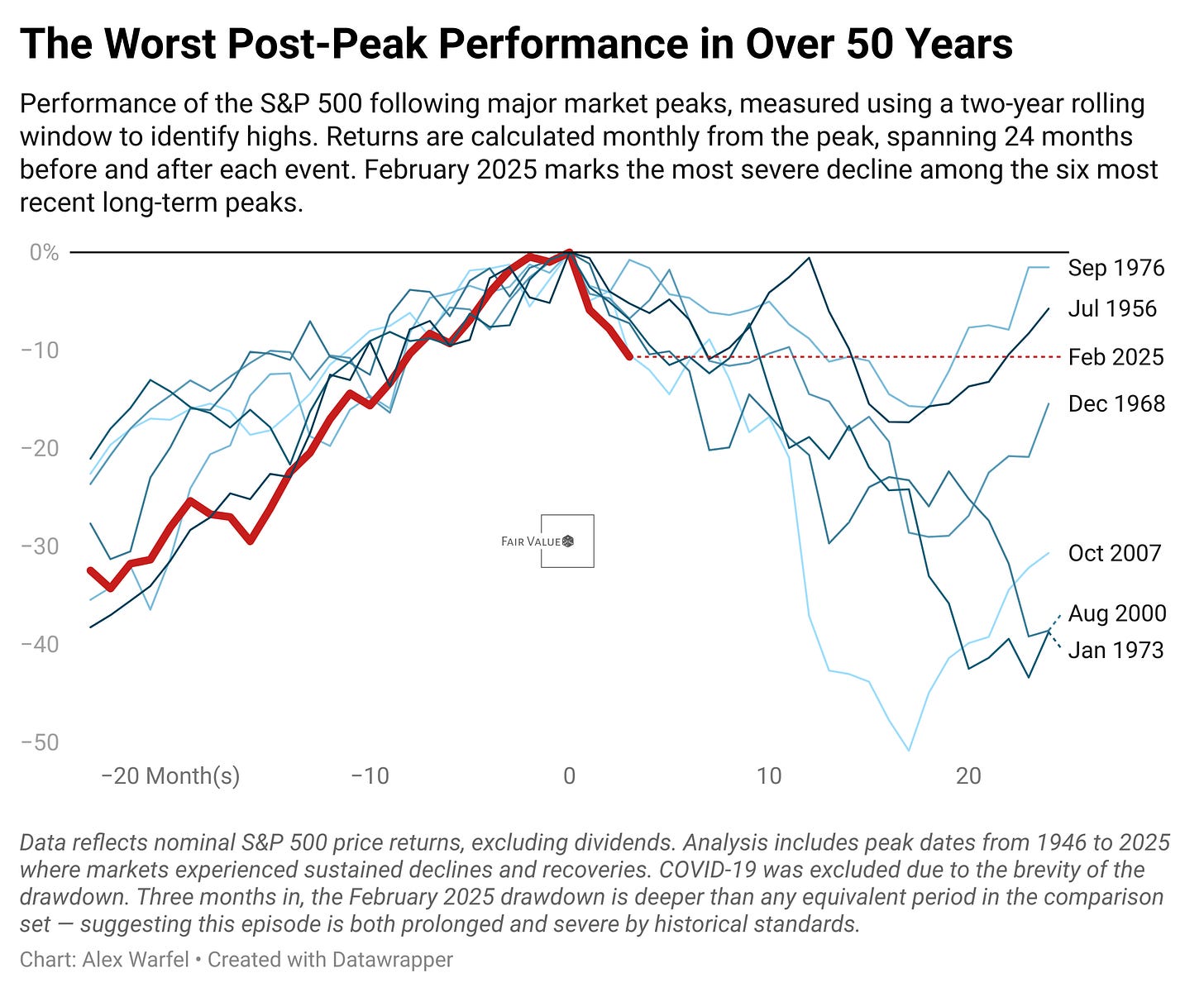

Chart of the Week: The current market downturn since February 2025 is already the worst post-peak performance of the S&P 500 in over 50 years, largely driven by uncertainty around the Trump administration’s tariff policies.

Beyond Bias: Choice-supportive bias causes investors to irrationally justify poor financial decisions, but research shows structured self-reviews and decision journaling significantly improve objectivity.

Building Wealth: Spending money to reclaim time from daily tasks improves life satisfaction and reduces stress more effectively than income increases.

Historical Perspective: The first recorded sovereign bond default occurred in ancient Athens around 377 BC when military overspending led to unrepayable temple-backed loans.

Literature Review: Mutual fund managers reduce risk-taking by 6.82% during their zodiac years due to superstition, highlighting that even professional investors are vulnerable to irrational behaviors.

Chart of the Week: Navigating the Aftermath of Market Peaks—Why This Downturn Stands Out

This chart underscores the severity of the current market downturn, showing that, as of April 2025, the S&P 500 has experienced the worst performance following a major market peak in over 50 years. Such extended downturns often lead to increased market volatility and investor uncertainty, factors well-documented to deter capital expenditures and long-term business investments (Bloom, 2009; Baker et al., 2016). Empirical research indicates that heightened trade tensions and tariff uncertainty significantly depress corporate investment, as companies pause major decisions due to unclear policy environments, effectively putting economic growth into a holding pattern (Handley & Limão, 2017; Amiti et al., 2019). Given the current administration’s aggressive tariff stance, markets are unlikely to stabilize until there’s greater policy clarity, signaling investors may continue facing elevated volatility in the near term.

Beyond immediate market impacts, prolonged downturns also damage investor confidence, reshaping how businesses perceive risk and returns in the U.S. market. Evidence from past tariff-related episodes shows that even temporary protectionist policies can produce lasting negative consequences for investor perceptions, undermining the credibility of policy commitments and fueling long-term uncertainty (Fajgelbaum et al., 2020). The severity of this current decline relative to previous downturns suggests we may be witnessing a shift in sentiment about the reliability of U.S. economic policy, which could prompt firms—both domestic and international—to reconsider their long-term capital allocation strategies away from the U.S., at least until stable policy expectations are restored (Caldara et al., 2020). Consequently, the path forward for U.S. markets heavily depends on the administration’s next moves regarding tariffs and its broader approach to international economic relations.

Beyond Bias: Choice-Supportive Bias — Why We Defend Our Dumbest Financial Decisions

Choice-supportive bias is the tendency to justify past decisions by selectively recalling their positive aspects—even when the outcome was objectively poor. Once we commit to a choice, we subconsciously rewrite history to make it seem like the right call. This bias has been well-documented in cognitive psychology: Mather et al. (2000) found that people remember positive features of chosen options more clearly than those of rejected alternatives, regardless of actual results. In investing, this can show up as emotional attachment to a stock that underperformed, or a lingering belief that “I was early, not wrong.” It fuels overconfidence in flawed theses, discourages introspection, and encourages portfolio inertia—even when the rational move is to pivot.

To protect against choice-supportive bias, investors need structured self-review and decision journaling. Research by Fischhoff and Beyth-Marom (1997) shows that ex-ante reflection—writing down your rationale before making a decision—creates a clearer benchmark for post-hoc evaluation. When you record why you made a trade, what outcome you expected, and what risks you considered, you gain a more objective lens through which to assess results. A quarterly review of your past trades—especially the losers—can reveal patterns of self-deception. Did you exit too late? Hold out of pride? Rationalize bad performance as “temporary”? Tools like post-mortems, trading diaries, or even a “bad trade autopsy” session help create friction between memory and myth. In short: the more structure you add around reflection, the harder it becomes to lie to yourself.

Building Wealth: Buy Time, Not Stuff — Why the Highest-ROI Asset Is Attention

One of the most overlooked levers in personal finance isn’t a financial product—it’s time. A 2017 study by Whillans et al., published in PNAS, found that individuals who spent money to “buy time”—by outsourcing daily tasks like cleaning, grocery runs, or meal prep—reported significantly higher levels of life satisfaction and lower stress, even when controlling for income. Crucially, this held true across a range of socioeconomic groups. The researchers argue that time scarcity—the feeling of constantly being rushed—is a stronger predictor of lower well-being than low income. This aligns with the findings of Kahneman and Deaton (2010), who showed that while income increases life evaluation, it has diminishing returns for emotional well-being. In other words: earning more only helps up to a point—reclaiming attention is what makes it sustainable.

To implement this as a DIY investor, treat time as a capital allocation decision. Ask yourself: “Where do I spend an hour that produces zero future value—and can I delegate it?” Consider outsourcing tasks that cost less than your effective hourly rate or consume your highest-energy hours. Studies on cognitive bandwidth (Mullainathan & Shafir, 2013) suggest that mental load from small but recurring tasks reduces decision quality over time. Freeing up even one or two hours per week can compound—not in the market, but in your clarity, creativity, and capacity to make better financial decisions. Time is finite. Treat it like the asset it is.

Add to your Toolbelt

Take control of your financial future with Rainier FM—your AI-powered financial planning companion. FM stands for Financial Model, and that’s exactly what this app delivers: optimized, data-driven financial plans tailored to your goals. Using advanced optimization techniques and AI-driven insights, Rainier FM helps users navigate everything from retirement planning to wealth building with confidence. Pricing reflects the cost of running the service, but I’m actively gathering feedback to refine and improve it. Here’s an example of an insight this app can help you uncover.

If this sounds like something you’d find valuable, feel free to reach out or sign up—I’d love to hear what you think as I continue developing the platform!

Historical Perspective: The First Bond Default Wasn’t Argentina—It Was Athens

When investors think of sovereign debt crises, they tend to picture Argentina in 2001, Greece in 2010, or Russia in 1998. But the first known government bond default occurred over two thousand years earlier—in ancient Greece, around 377 BC. At the time, Athens led the Delian League, a powerful alliance of city-states that had pooled naval resources and capital to defend against Persian expansion. To fund its increasingly ambitious (and expensive) military campaigns, Athens began issuing debt backed by temple treasuries—specifically, loans from the Temple of Athena and other sacred sites, considered the most secure financial entities of the day.

These weren’t just symbolic notes. Records carved into stone show that Athenian temples lent substantial silver reserves to the state with the expectation of repayment and interest. But as war costs ballooned and Athenian control over the league began to wane, the city failed to make good on its obligations. By 354 BC, inscriptional evidence suggests these “holy loans” were effectively written off. The first sovereign default in recorded history didn’t involve a central bank, credit ratings, or bond auctions—but it had the same root causes we see today: unsustainable debt loads, geopolitical overreach, and misaligned incentives between fiscal and religious institutions.

The Athenian default is more than a historical curiosity—it’s a blueprint for how empires overshoot. As classicist Edward Cohen has noted, these early loans were likely issued under duress, framed as “religious obligations” to pressure temples into compliance. Once Athens lost military dominance, creditors had little recourse. This mirrors a common dynamic in sovereign finance: nations borrow from the institutions they control, but the illusion of creditworthiness fades quickly once power shifts. The same dynamic played out with French assignats, Soviet war bonds, and arguably, China’s shadow banking today.

For investors, the lesson is structural. Sovereign debt crises aren’t black swan events—they’re the downstream result of long-term fiscal and geopolitical choices. Just as Athens borrowed from its temples, modern states borrow from retirement accounts, central banks, and foreign governments. When wars or entitlements outpace revenues, something breaks. The question isn’t if the debt becomes a problem—it’s when, and who gets hurt first.

Supporting Research

Cohen, Edward E. Athenian Economy and Society: A Banking Perspective. Princeton University Press, 1992.

Millett, Paul. Lending and Borrowing in Ancient Athens. Cambridge University Press, 1991.

Harris, William V. War and Imperialism in Republican Rome, 327–70 B.C. Oxford University Press, 1979.

Davies, Glyn. A History of Money from Ancient Times to the Present Day. University of Wales Press, 2002.

Finley, M. I. Politics in the Ancient World. Cambridge University Press, 1983.

Literature Review: Superstition and Risk in Professional Investing — What Zodiac Years Reveal About Fund Managers

In a sweeping new study, Chen, Li, Rau, and Yan (2025) uncover a fascinating psychological vulnerability in mutual fund managers: superstition. Analyzing a dataset of over 12,000 fund-year observations in China from 2005 to 2023, the authors find that fund managers reduce risk-taking by an average of 6.82% during their zodiac years — years that align with their birth year in the Chinese lunar cycle and are traditionally seen as unlucky. This effect is strongest among less experienced managers, those without finance degrees, and those with weaker prior performance. Not only do these managers shift away from risky stocks and toward fixed income during these periods, but they also display lower trading aggressiveness and more diversified portfolios. The authors argue this behavior is not random: superstition measurably alters investment decisions — even among professionals assumed to be rational by design.

To test their hypothesis, the authors use rigorous methods, including multiple risk proxies (portfolio volatility, tracking error, standard deviation of returns), placebo tests with “fake” zodiac years, and propensity score matching. They further employ a Difference-in-Differences with Multiple Groups (DIDM) framework to correct for staggered treatment effects and show that only the true zodiac year drives the decline in risk-taking. Perhaps most striking is that this drop in risk is not harmless: fund performance declines in zodiac years as well, suggesting that managers become too conservative in response to superstition. And when managers exit or enter during a zodiac year, fund risk adjusts accordingly — further strengthening the causal claim.

This paper builds on a broader behavioral finance literature that challenges the retail/professional investor divide. Prior work has shown that individual investors are more likely to trade on lucky numbers (Bhattacharya et al., 2018), buy on auspicious days (He et al., 2020), or pay premiums for “lucky” packaging (Block & Kramer, 2018). But this study shows that even seasoned institutional players aren’t immune. The key moderating variables — experience, education, skill, and investment autonomy — mirror patterns in other research on bias suppression (Berk & van Binsbergen, 2015). Importantly, even skilled managers can revert to irrational behaviors under stress: superstition’s effect intensifies during periods of high policy uncertainty, a finding that aligns with behavioral models of stress-based heuristics (Kumar, 2009).

For DIY investors, the lesson is not to avoid mutual funds — but to recognize that even professional managers are subject to the same emotional circuitry we all have. Fund performance is shaped not just by market conditions, but by the mental state and belief systems of the people behind the trades. This study suggests that newer managers or those in more passive or flexible funds may be more vulnerable to bias, especially during times of volatility. Investors evaluating fund managers should go beyond past returns and expense ratios to consider the behavioral stability of the investment process — factors like team structure, management turnover, and the manager’s career stage can subtly shape outcomes. More broadly, the paper is a reminder that behavioral finance is not just a quirk of individual investors — it’s a foundational part of how markets work, even at the institutional level.

Curious about money, investing, or the economy?

I occasionally answer reader questions in the newsletter—no jargon, just thoughtful, practical insight. If something’s on your mind, tap the button below to send it in anonymously.