America’s Economic Momentum: Why the U.S. Keeps Outpacing the World

Despite global uncertainty, the U.S. economy has remained resilient—outpacing its peers in growth, innovation, and energy independence.

Today’s article takes 14 minutes to read.

Key Takeaways

In the news: Mass Federal Layoffs Could Shake the Job Market – Up to 475,000 federal jobs may be lost through hiring freezes, resignations, and firings, with Washington, D.C., Maryland, and Virginia hit hardest. The impact could extend to contractors and local businesses reliant on government spending.

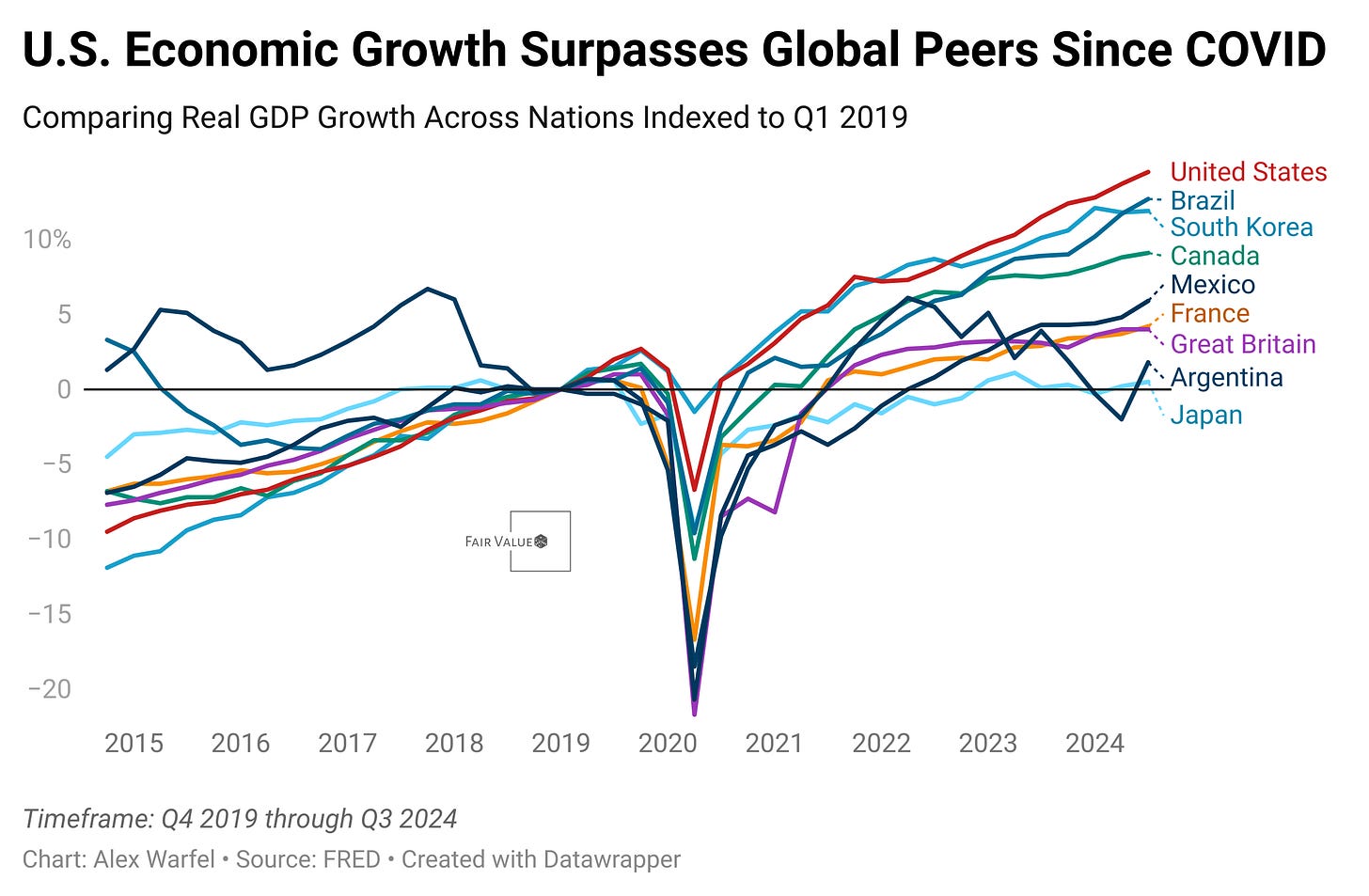

Chart of the week: U.S. Economic Growth Has Outpaced Other Nations – The U.S. has experienced stronger GDP growth post-COVID than many developed countries, thanks to aggressive fiscal stimulus, a stable energy supply, and a thriving innovation sector.

Beyond bias: Recency Bias – Investors and homebuyers often overreact to recent trends, ignoring long-term cycles. Research shows that markets tend to mean-revert over time, making emotional, short-term decisions costly.

Building wealth: The Future Purchase Rule to Curb Impulse Spending – Studies show that delaying purchases for 30 days significantly reduces unnecessary spending while improving long-term financial discipline.

Historical perspective: Medieval Ireland’s Honor-Based Economy – Wealth was measured by honor price rather than currency, and debts were repaid through cattle, land, or social obligations. This system provided social stability but reinforced rigid hierarchies and limited economic mobility.

Literature review: Fear, Not Risk, Drives Market Behavior – A new study challenges traditional asset pricing models, showing that investor sentiment and fear have a greater influence on market returns than risk-based factors like beta and the equity risk premium.

Have a question?

I’m adding something new this week—reader Q&A. If you have a question about the economy, investing, financial decision-making, or historical finance, submit it anonymously using the form below. Each week, I’ll pick one question and provide a detailed response in the next newsletter.

This isn’t financial advice, but I’ll break down ideas, provide deeper research, and share insights on topics you’re curious about. If you accidentally include personal details, I’ll remove them and keep the discussion hypothetical.

No question is too big or too small—if you’re wondering about something, chances are others are too. Submit your question here, and I’ll tackle it in the next edition!

In the news

Mass Federal Layoffs Could Shake the Job Market

The federal government is cutting jobs, with up to 475,000 positions potentially on the line through hiring freezes, resignations, and firings.

While this represents only about 0.3% of total U.S. jobs, the regional impact could be severe, especially in places like Washington, D.C., Maryland, and Virginia, where federal jobs are a major part of the economy.

Job cuts could ripple out to contractors and local businesses that rely on government workers as customers.

Many federal workers have specialized skills, making it harder for them to transition into new roles, which could prolong unemployment in affected areas.

If you’re job hunting in government-heavy regions, expect more competition and slower hiring.

Housing Market: Buyers Are Finally Getting Some Leverage

After years of bidding wars and soaring prices, home buyers are starting to regain negotiating power.

More homes are sitting on the market, and the typical home now sells for about 2% below asking price.

In high-inventory areas like Florida, sellers are throwing in extras—like furniture, home-theater systems, or repairs—to close deals.

However, home prices are still high, and mortgage rates are near 7%, making affordability a challenge despite better negotiating conditions.

If you’re buying: You might get a price cut or seller concessions, but financing costs remain steep.

If you’re selling: Be prepared to wait longer, lower your price, or sweeten the deal.

Tariffs Could Raise Energy Bills and Delay Grid Upgrades

The U.S. power grid is already under strain, especially with rising demand from AI data centers.

Transformers—critical equipment for power distribution—are in short supply and could get even more expensive due to new tariffs on steel, aluminum, and possibly copper.

Transformer prices have already jumped 70%-100% since 2020, and additional tariffs could push them up another 8%-9%.

Why this matters: If it becomes harder to expand and modernize the grid, electricity prices could rise further—and outages could become more frequent.

Some areas, like New Jersey, are already seeing projected utility bill hikes of 17%-20% this summer.

How This All Ties Together

The economy is facing pressure from multiple directions at once. Job cuts could hurt spending, especially in regions reliant on government employment. Housing affordability is improving slightly for buyers, but interest rates remain high. Meanwhile, energy costs—already rising—could climb even more if trade policies make grid upgrades more expensive.

If you’re navigating these shifts, focus on controlling what you can:

If you’re in a government-related industry, it may be worth diversifying your job options.

If you’re buying a home, negotiate aggressively—but consider whether high interest rates will offset any price discounts.

Keep an eye on your utility costs—with energy prices on the rise, cutting back on consumption might help.

Chart of the week

The United States has demonstrated remarkable economic growth since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, outpacing many other developed nations. This resilience can be attributed to several key factors. Firstly, the U.S. implemented substantial fiscal stimulus measures during the pandemic, providing direct income support to households and businesses. This approach not only sustained consumer spending but also preserved employment levels, leading to a swift economic rebound. In contrast, many European countries opted for more conservative fiscal responses, resulting in slower recoveries.

Moreover, the U.S. economy benefits from a diversified energy sector, reducing its vulnerability to global energy price fluctuations. While Europe faced significant economic challenges due to high energy costs, especially amid geopolitical tensions, the U.S. maintained more stable energy prices, insulating its economy from such shocks. Additionally, America’s robust culture of innovation and entrepreneurship has fostered technological advancements and productivity gains, further propelling economic growth. This environment encourages investment and attracts talent, reinforcing the nation’s economic exceptionalism.

Beyond bias

Recency bias is the tendency to place too much weight on recent events while ignoring long-term historical trends. This cognitive distortion leads investors, homebuyers, and policymakers to make decisions based on short-term patterns rather than broader cycles. In investing, for example, individuals often chase performance, assuming that a stock or asset class that has recently performed well will continue to do so indefinitely. Research by Barber and Odean (2013) found that retail investors frequently buy stocks after strong recent performance and sell after declines, despite evidence that markets tend to mean-revert over time. Similarly, in the housing market, homebuyers often assume that rapid price increases signal continued appreciation, leading to speculative bubbles like the 2008 housing crisis (Shiller, 2005). Conversely, after a crash, recency bias causes excessive pessimism, leading investors to avoid stocks or homes even when valuations become historically attractive. This bias distorts risk perception, making people overly confident during booms and excessively fearful during downturns.

To counter recency bias, investors and decision-makers must adopt a long-term perspective grounded in historical data rather than emotional reactions to recent trends. One effective strategy is to analyze financial markets and economic cycles over decades rather than months. Studies show that disciplined investors who maintain a diversified portfolio and rebalance regularly outperform those who make short-term reactive trades (Basu, 1977). Similarly, in real estate, looking at fundamental indicators—such as wage growth, housing supply, and interest rates—rather than just recent price changes can prevent irrational decision-making. Automated investment strategies, such as dollar-cost averaging, can also help by removing emotions from the equation and ensuring that investments are made consistently regardless of market fluctuations (Thaler & Benartzi, 2004). By shifting focus from recent movements to historical context, investors can avoid the trap of short-term thinking and make more rational financial decisions.

Building wealth

Impulse spending is one of the biggest obstacles to building long-term wealth. The Future Purchase Rule is a simple but powerful way to combat this by introducing a waiting period before making non-essential purchases. Instead of buying something on impulse, you commit to waiting at least 30 days before making the decision. This method works because it gives your brain time to separate short-term desire from genuine need. Research in behavioral psychology suggests that delaying gratification reduces impulse spending and increases financial satisfaction (O’Donoghue & Rabin, 1999). By stepping back and evaluating whether a purchase truly aligns with your goals, you naturally reduce wasteful spending while keeping your financial priorities intact. Often, you’ll find that after 30 days, the urge to buy has faded, allowing you to redirect that money toward investments, savings, or experiences that bring lasting value.

To implement this strategy, create a “future purchases” list where you write down any non-essential item you want to buy, along with the date you first considered it. Then, set a reminder to review the item 30 days later. If you still want it and can justify the expense, go ahead—but in many cases, you’ll realize you don’t need it as much as you initially thought. For added effectiveness, consider pairing this method with a budget rule, such as allocating a fixed percentage of discretionary income toward future purchases. This not only controls impulse spending but also makes you more intentional about what you buy. Over time, this practice builds financial discipline, keeps more money in your investment accounts, and helps shift your mindset from instant gratification to long-term wealth creation.

Product focus

Take control of your financial future with Rainier FM—your AI-powered financial planning companion. FM stands for Financial Model, and that’s exactly what this app delivers: optimized, data-driven financial plans tailored to your goals. Using advanced optimization techniques and AI-driven insights, Rainier FM helps users navigate everything from retirement planning to wealth building with confidence. Pricing reflects the cost of running the service, but I’m actively gathering feedback to refine and improve it. If this sounds like something you’d find valuable, feel free to reach out or sign up—I’d love to hear what you think as I continue developing the platform!

Historical perspective: The Honor-Based Economy of Medieval Ireland

In medieval Ireland, wealth and financial standing were not measured in gold or coin but in honor price—a system that tied economic value to personal reputation and social status. Instead of using standardized currency, debts and legal disputes were settled through cattle, land, or obligations owed to the community, a system deeply embedded in the Brehon Laws, Ireland’s ancient legal code. At the heart of this system was the idea that a person’s financial worth was directly linked to their honor, and any debt or wrongdoing required compensation proportional to their standing. If an individual caused harm—whether through theft, injury, or insult—the restitution paid (called Éraic, a form of wergild) was based on the victim’s social rank. This system ensured that economic exchanges weren’t just financial transactions but also mechanisms for maintaining social harmony and accountability.

One of the most striking aspects of this system was its communal nature. Debt was not viewed as an individual burden but as a responsibility shared by the entire family or clan. If someone could not afford to repay a debt, their extended family stepped in, ensuring that no one was left destitute and that lenders could still expect repayment. This structure had its benefits: it provided a social safety net, reduced extreme poverty, and encouraged responsible financial behavior. Unlike modern credit-based economies, where a single financial misstep can ruin an individual’s future, medieval Ireland’s debt structure ensured that economic hardship was absorbed collectively, preventing wealth from accumulating solely in the hands of the few. However, this also meant that personal financial failure could bring shame upon an entire lineage, reinforcing rigid social hierarchies and discouraging risky innovation that might lead to failure.

While the system fostered social cohesion, it also had significant drawbacks. Because honor price was tied to birth and status rather than merit, wealth distribution was highly unequal, with the noble class holding economic advantages over commoners. Unlike in market-driven economies where individuals can theoretically rise up through innovation and entrepreneurship, the honor-based system limited upward mobility—a person’s financial potential was largely determined by their lineage rather than their skills or ambitions. Additionally, the reliance on barter and non-monetary transactions made trade beyond local communities difficult. While an honor-based economy worked well within close-knit societies, it struggled to adapt to the increasing complexities of medieval European trade networks, where coins, standardized credit, and banking systems were emerging as dominant economic forces.

The remnants of this system can still be seen in modern finance, particularly in reputational lending and credit scores, where a person’s financial trustworthiness is evaluated based on past behavior rather than just their current assets. The idea of shared financial responsibility also has echoes in today’s microfinance models, where community-backed lending groups support individuals who lack traditional credit access. However, unlike medieval Ireland, modern economies prioritize individual financial autonomy, meaning that personal debt no longer carries the same communal obligations or reputational weight. The shift from honor-based economies to formal banking systems has allowed for greater economic expansion and social mobility, but it has also removed some of the built-in social protections that once ensured no one was left behind. While medieval Ireland’s financial system was far from perfect, it offers an interesting counterpoint to today’s debt-driven economy—one where wealth was tied not just to assets but to the respect one commanded in society.

Supporting Research:

Kelly, Fergus. A Guide to Early Irish Law. Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1988.

Gibson, James L. The Brehon Laws: A Legal Handbook. Hodges, Foster & Figgis, 1865.

Doherty, Charles. “Honor Price and Economic Stability in Medieval Ireland.” Irish Historical Studies, vol. 32, no. 126, 2001, pp. 145–167.

McLeod, Neil. “The Concept of Éraic in the Early Irish Legal System.” Celtica, vol. 23, 1997, pp. 78–102.

Literature review

Fear, Not Risk, Explains Asset Pricing

For decades, asset pricing theory has been dominated by the idea that risk determines returns, but a new paper by Rob Arnott and Edward McQuarrie challenges this assumption. The authors argue that fear—both fear of losing money and fear of missing out (FoMO)—is a stronger force in driving market behavior than traditional risk measures. By analyzing over two centuries of market data, the study highlights multiple empirical failures of risk theory, particularly its inability to consistently explain excess equity returns. Historical evidence shows that investors have often accepted lower-than-expected returns on stocks and, at times, have earned returns far beyond what risk theory would predict. The paper suggests that these anomalies are better explained by investor sentiment, herd behavior, and emotional decision-making rather than purely rational risk-reward trade-offs.

The study examines long-term asset returns across multiple markets and finds that traditional models like the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) fail to account for significant variations in returns. The so-called “equity risk premium”—the excess return stocks should provide over risk-free bonds—has been inconsistent across time periods and markets. For example, U.S. stock investors in the 1800s often underperformed long-term government bonds for decades at a time, contradicting the assumption that stocks always reward higher risk. Additionally, international data shows that in 18 out of 19 markets studied, there were periods of at least 30 years where bonds outperformed equities, further undermining risk-based explanations for market returns. The authors argue that fear-driven investor behavior—whether in the form of panic selling during downturns or euphoric buying during bubbles—creates pricing anomalies that persist despite decades of research trying to rationalize them within risk-based models.

Perhaps the most striking evidence comes from the study’s examination of factor investing. While early research suggested that small-cap (stocks that have a market capitalization of less than $2 billion) and value stocks (stocks that have a low price to earnings ratio relative to other stocks) offered a premium for their additional risk, more recent data has shown that these excess returns are unreliable, and in some cases, have disappeared entirely. The authors highlight how the 1992-2024 period upended the expectations set by earlier decades, with small growth stocks significantly underperforming and large growth stocks outperforming their riskier counterparts. This inconsistency suggests that investor psychology—fear of missing out on trends like tech stocks, for example—plays a major role in asset prices. The paper also points out that if fear is the dominant force in investing, there can be no truly “safe” asset. Even cash, often assumed to be risk-free, carries hidden dangers, such as inflation eroding its purchasing power, making it just as susceptible to shifts in investor sentiment as stocks and bonds.

The implications for DIY investors are profound. If fear, not risk, is the primary driver of returns, traditional portfolio strategies that rely on risk-based models may be fundamentally flawed. Instead of relying purely on risk metrics like beta or Sharpe ratios, investors should pay close attention to market sentiment, behavioral biases, and their own emotional responses to investing. Recognizing the power of fear—whether it’s panic selling in downturns or chasing hype-driven assets—can help individual investors make better decisions, resist market hysteria, and maintain a disciplined approach. The authors do not dismiss risk outright but argue that risk theory alone has done a poor job of explaining market returns. By incorporating a fear-based framework, investors may gain a more realistic understanding of how markets behave and avoid falling into the traps that have led to so many historical investment mistakes.